Selections From the Prophets Week 10

Jonah (Postexilic): A Tale of Two Cities: Jonah 3:6–10

By Jeffrey Keuss

Professor of Christian Ministry, Theology, and Culture

Read this week’s Scripture: Jonah 3:6–10

12:09

![]() Enlarge

Enlarge

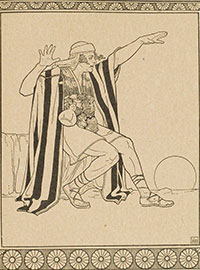

When the news reached the king of Nineveh, he rose from his throne, removed his robe, covered himself in sackcloth, and sat in ashes. Then he had a proclamation made in Nineveh: “By the decree of the king and the nobles: No human being or animal, no herd or flock, shall taste anything. They shall not feed, nor shall they drink water. Human beings and animals shall be covered in sackcloth, and they shall cry mightily to god. All shall turn from their evil ways and from the violence that is in their hands. Who knows? God may relent and change his mind; he may turn from his fierce anger, so that we do not perish.” When God saw what they did, how they turned from their evil ways, God changed his mind about the calamity that he had said he would bring upon them; and he did not do it. (3:6–10)

As mentioned in our introduction to the Prophets, one of the things that ironically unify the prophetic literature is the diversity we find. In all but one book of the Prophets, the major theme is found in the message of God given to the prophet and then spoken through the prophet to Israel. However, sometimes the message is framed on behalf of the people through the prophet towards God, as in Habakkuk, and other times the message is addressed in part to a foreign nation or nations in addition to Israel.

In Jonah we have a very different account: more than anything it is the story of a person and not the report of a message in isolation. In this way, Jonah stands in stark contrast to the other prophets — to use cultural critic Marshall McLuhan’s famous statement, “the medium is the message.” Because Jonah is a book confirmed in our canon of Scripture, we are to conclude that it isn’t so much what Jonah says but what happens to Jonah that is indeed the message. As Old Testament scholar David Hubbard states rather pithily, “The story involves much more than being swallowed by a fish.” [Author’s Note 1]

Few stories found in the Old Testament have the enduring cultural impact of Jonah. The notion of this prophet running from God, being thrown overboard in a storm, being swallowed by a large sea creature, and eventually being spewed forth on the shores in order to bring judgment on Nineveh has framed the collective cultural imagination from Pinocchio to Moby Dick to the Veggie Tales movies. Pastor, best-selling author, and 1954 graduate of SPU Eugene Peterson has said that in his many years of ministry, Jonah was always a favorite, and in studying it he found that “It was just as interesting in Hebrew as it was on flannelgraph.” He notes:

One reason for the long-run popularity of Jonah is that it invites playfulness. The book of Jonah both in content and in style is playful. And it invokes playfulness in us. [Author’s Note 2]

Reading Jonah leaves many readers with a number of events that go beyond the rational. The story continues to push the limits of the reader’s ability to believe — the immediacy of Jonah’s running to Tarshish without an afterthought, the surreal events on the ocean, the fantastical swallowing by a sea creature, and the vomiting of Jonah alive on the shoreline. As David Hubbard states:

A firm principle in biblical study is that, even in a clearly historical passage, the theological message is more important that the historical details. The Bible was not written to satisfy curiosity about peoples and events in the ancient Near East. It was inspired by God’s Spirit, with doctrinal, spiritual, and moral intent. As part of the biblical canon, Jonah must be studied with primary attention to the theological message. At this point the historical and parabolic interpretations come together, for either approach yields the same lesson: Yahweh is concerned about pagan peoples and commands his servants to proclaim his message to the nations. [Author’s Note 3]

“Now”

We know fairly little of Jonah’s past. He is Jonah ben Amittai, and as we hear in 2 Kings 14:25, he lived during the expansion of Israel in the days of Jeroboam II. When we begin the story, we are not looking back over our shoulders but are introduced to Jonah as someone already on the run straight ahead at full speed. For modern readers it is akin to walking into a movie after the credits have rolled and the first car chase is in high gear.

Eugene Peterson mentions that the first word in Jonah is the Hebrew word translated “Now it once happened,” which is “a formula for the beginning of stories in which the confronting event of God’s word shapes the narration.” [Author’s Note 4] This “now” is like a gunshot at the beginning of a footrace, and we find Jonah running the race very much alone. He hears the words of God’s call, which are in keeping with the mode of prophetic call that we discussed in an earlier Lectio:

Go at once to Nineveh, that great city, and cry out against it; for their wickedness has come up before me. (1:2)

Yet, as we hear in the next verse, Jonah exercises the freedom of the prophetic call and immediately seeks to run away from it:

But Jonah set out to flee to Tarshish from the presence of the Lord. He went down to Joppa and found a ship going to Tarshish; so he paid his fare and went on board, to go with them to Tarshish, away from the presence of the Lord. (1:3)

Tarshish — the Land Far, Far Away

In Under the Unpredictable Plant, Eugene Peterson situates the importance of Tarshish in the Hebrew imagination as a romantic place of escape and an idealized destination point that was exotic beyond compare. Referencing Hebrew scholar Cyrus Gordon, Peterson sees the city of Tarshish representing a romantic “far-off and sometimes idealized port” and a “distant paradise” [Author’s Note 5] that was an emotional and spiritual escape noted in 1 Kings 10:22 as being vibrant, prosperous and exotic with riches as diverse as “gold, silver, ivory, apes, and peacocks.” In many respects, we can think of Tarshish as a fairy tale land, a land “far, far away.” Although it is very much a real location, it is a place that represents all our fantasies. It is a place we can go to in our minds when we are stressed, a place where there are no troubles and no one is asking anything from us that can’t be solved by the wave of a magic wand or the sprinkling of fairy dust. When Jonah hears God’s call, he immediately decides not to follow his vocation but to go on vacation. However, the zip code Jonah’s prophesy points to is not in a fantasy land “far, far away,” but in the very real city of Nineveh.

Nineveh— Far Away yet So Close

What is often overlooked in reflections on Jonah is the very real context of the city the prophet is called to prophesy to: Nineveh. Of all the characters in the four chapters that constitute Jonah’s prophecy (if we can think of Nineveh as a character), the city of Nineveh is second only to the Lord God in its ability to surprise us.

As we have seen through our readings of the prophets in past Lectios, places matter to the prophets. Each prophet is called to speak into and represent God in very particular places. They are called to cities to be rebuilt from ruin as in Jerusalem, or places of captivity, such as Babylon. Nineveh is such a place.

As we hear in 3:3, “Nineveh was an exceedingly large city, a three days’ walk across,” and as such we have a city of great power and prominence in the region. In Genesis 10:12, Nineveh is referred to as “that great city,” as it sits in relation to the ancient cities of Rehoboth-Ir, Calah, and Resen.

Nineveh is also a city that is ethnically distinct from Israel, which underscores the racial and cultural tension that is a backdrop for this tale. Not only is Nineveh powerful, but in Jonah’s eyes its inhabitants are foreigners, not part of God’s chosen people. As my colleague Dr. Sara Koenig reminded me in relation to the importance of knowing the context of Nineveh, we need to consider that Nineveh is the capital of Assyria, which defeated the Northern Kingdom in 722 B.C.E. If this is postexilic text [Author’s Note 6] as many scholars attest, then Jonah’s call is tantamount to asking a Jew to walk into the halls of Berlin in the 1940s. Add to the fact that Nineveh completely submits to God’s judgment regardless of the outcome — and we are given a bold picture of the unsurpassing and unexpected love of God that arises in places and people we least expect.

Pāneh — the Face of the Lord

In our reflections on the prophet Ezekiel, we noted that God tells the prophet, “set your face toward [Jerusalem]” in order to stand as a witness to the judgment of God (Ezekiel 4:3), which resonates with Jesus as he “set his face to go to Jerusalem” (Luke 9:51). As we encounter the prophecy of Jonah, we find that “set his face” takes on yet another dimension. As in the first chapter, we hear that Jonah is fleeing the presence of the Lord. The Hebrew word for “presence” (pāneh) is the same as the word for “face,” so it could be said that Jonah is fleeing from “the face of the Lord,” a translation that better gets at Jonah’s posture towards God. Jonah is fleeing the intimacy, accountability, and risk that come from being close enough to see eye to eye, to dwell in the intimacy of another without coverings, without defenses, without restraint. It is a very vulnerable call to be in the pāneh of the Lord. That Jonah is being called to go to Nineveh — and not a fantasy land like Tarshish — in order to find this intimacy speaks volumes about where we as well are called to meet and encounter God.

Vacation or Vocation?

One of the most fantastical parts of this “whale of a tale” is the complete and utter repentance of a powerful nation before the God of the universe — both parties acting in ways that Jonah never saw coming and could experience only by submitting to God’s call to go to the place and people God specified. As we have heard, this is a tale of two cities. One is a journey of getting “far, far away” from the call of God — a “vacating” from one’s true calling — and the other is a “faraway yet so close” encounter with the face of God in the faces of those God calls us to — a “vocation” of deep intimacy from the deep voice of God.

Which city will you choose to journey to when you hear God calling you to go?

Questions for Further Reflection

- Many assert that Jonah’s experience with God is meant to communicate more than his actual message. What do you learn about what it means to be in relationship with God from your most recent reading of this prophetic text? What do you learn about the character of God Himself?

- Jonah is being called to face a people who are his enemies, as well as people who are able to heed God’s call in ways that Jonah himself has yet to do. Are there groups of people you consider far outside your community of comfort and acceptability whom you would be surprised to see God working through? Who would those people be?

- In thinking about people who would be your own “Nineveh” — consider writing a prayer for them. What would you write?

- The Lectio writer notes that Jonah escapes on the boat in favor of “vacation” over “vocation.” Have you ever experienced such a turn in your own relationship with God? What happened afterward? If you’re currently experiencing this type of season, spend some time in prayer over how God might be calling you back into your true calling.

<<Previous Lectio Back to Selections From the Prophets Next Lectio>>

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons License.