Romans Week 5

Justification and Sanctification: Romans 5–6

Seattle Pacific University Professor of Dogmatic and Constructive Theology

Read this week’s Scripture: Romans 5–6

16:20

Enlarge

Enlarge

“What’s in a name? That which we call a rose

By any other name would smell as sweet.”

So states Juliet in Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet. This young lady was waxing philosophical in that she could not understand how the names of her and her lover’s families could cause such strife when really what mattered was not people’s names but their character, who they are.

Juliet’s specific situation made it so that she felt that names got in the way of what was important — labels got in the way of true love. To a certain degree, we can sympathize with Juliet. Names do get in the way at times, especially when they occasion violence, oppression, and systemic abuse. Just because some people hail from certain regions, classes, or races, and other people hail from others does not necessarily mean that we should lose sight of our common humanity and the matters that are important in life, including character, virtue, compassion, and the like.

The Importance of Names

But from another perspective, names are quite important. Let’s go back to Romeo and Juliet: Although these young and naïve lovers can’t see what the big fuss is about, their lives are not constituted solely by their individual, singular experiences. Their lives are given coherence and meaning through their personal stories and histories, through the ways they were raised and trained by their families and neighbors.

Romeo is a Montague through and through, whether he realizes it or not. He may have problems with the Montagues, he may wish things were different, but at the end of the day, he is a Montague; he thinks, feels, and values like a Montague, and although those traits are not evidenced (to him at least) in his love for Juliet, they are on display in more ways than he can see because being a Montague is his reality.

The same goes for Juliet and the Capulets. Certainly we can shape our realities to some degree, we have some level of self-determination, but we are also bound to our histories in important and sometimes elusive ways. Had Romeo and Juliet had children (spoiler; sorry), they would certainly have found ample occasions for recognizing the embeddedness of their identities in more ways than they would care to admit. I can just see the hypothetical scenarios now: Juliet would charge, “You have told me you are so different from your parents, but when Lil’ Romeo acted up today, you were your father chiding him!” — to which Romeo could respond, “You sound just like your mother right now.”

We may wish we had been raised in a different location with different parents and friends, but, at the end of the day, those experiences, and the labels and names that go with them, mark our identities in powerful ways.

If this is true with human experiences and relationships, it is all the more true with spiritual realities. We have noted that the gospel is for all, both Jew and Gentile, that God has been at work since the call of Abraham to bless the nations. All have sinned, all need this gospel, but the million-dollar question is: And what is the gospel? Furthermore, how does it take us from Point A (being alienated from God in our sins) to Point B (being reconciled with God, being at peace with God)? How can we describe such a transition, and what words, metaphors, and names do we use to narrate all of these happenings?

Justification and Peace

As noted earlier in Chapter 3, one of Paul’s favorite terms to describe all of this is justification. In our Bibles, this theme concludes Chapter 4 and is picked up in Chapter 5: “Therefore, since we are justified by faith, we have peace with God through our Lord Jesus Christ” (5:1).

Faith — believing and trusting in who God is and what God has done and is doing — allows for us to be at peace with God. We can boast as Christians with confidence not on the basis of what we have done or can do; rather on the basis of what God has done for us: “For while we were still weak, at the right time Christ died for the ungodly” (5:6).

The contrast in who God is and who we are reaches a fever pitch in 5:8: “But God proves his love for us in that while we still were sinners Christ died for us.” On its own terms, the word justification has a forensic or legal connotation — it literally means “to be declared just,” and so a person who is before a judge can be justified, or declared just, through legal proceedings.

This background is important to note. But it is equally, if not more, important to see how Paul uses the term justification. Within the context of Romans 5, he is using it alongside reconciliation and salvation; this usage suggests not simply that people are declared just (as with the forensic or legal connotation) but that people are “made right” or “brought into a right relationship” with God, with “right” here meaning “whole,” “upright,” “complete.” In other words, when Paul speaks of our “justification,” he is hinting at more than simply a legal pronouncement; he also has in mind the notions of covenant, peoplehood, and relationship.

Adam and Jesus

What Paul is touching on is even more grand than the story of Israel; now Paul is reaching back to account for the human condition as we know and experience it in the present: “Therefore, …sin came into the world through one man, and death came through sin, and so death spread to all because all have sinned” (5:12).

Paul is referring to the creation and fall accounts in Genesis 1–3 and makes a connection between Adam and Jesus. The logic is that just as sin and death came to the world through one man’s transgression, so salvation has now come through one man’s “act of righteousness.” Jesus functions as a “type” of Adam, a “second Adam,” reversing the curse of the fall. [see Author’s Note 1] Chapter 5 ends with the affirmation that sin abounded, but God’s grace abounded all the more. God’s remedy and God’s answer are greater than the original condition and curse of humanity.

But if we live this side of the fall but also this side of Jesus, how are we to think of sin? Should we continue to sin, allowing God the opportunity to show his grace time and time again? Again, Paul reverts to his hypothetical interlocutor so as to avert symptoms of “extreme-itis.”

Paul’s statement in 6:2, translated sometimes as “By no means!” or “Heaven forbid!” is a very strong expression, suggesting the ludicrousness of the suggestion. Paul goes on to make a very important and yet quixotic affirmation all the same. Post-fall, we are bound to sin and so are destined to die because of sin; post-Jesus, however, we are bound to Jesus and so destined to die to sin.

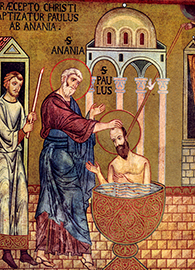

The logic is that we were cursed by the sin of Adam but now we have died and risen with Christ; we have been baptized into Jesus’ death, so that just as he has been raised from the dead, we can now walk in “newness of life” (6:4).

These are phenomenal considerations, especially when compared to lived experience. Anybody who has been a Christian for some time knows that being a Christian does not totally erase temptation, that it is possible to sin after one’s conversion and one’s baptism. And yet, Paul is making a status claim that those who are with and in Christ have died to sin.

EnlargeNo Longer Slaves to Sin

EnlargeNo Longer Slaves to Sin

Because of Jesus, we no longer have to be enslaved to sin (6:6); rather, we have available to us a new way of life in which we can live in the power of the resurrection. What Paul is emphasizing is that we do not have to approach sin after conversion the way we approached sin before conversion. Something changes in us, in our status, and in our reality. In Christ, we are new creatures.

This point is an important one, but one that many Christian traditions have had trouble acknowledging. Take, for instance, the Lutheran approach. Luther made the case that we are always simultaneously sinner and saint, that the struggle against the flesh is ongoing in this life until the new kingdom is established. Luther had a way of allowing Romans 5 to overshadow Romans 6 in that “justification by faith through grace” (Romans 5) could accommodate an internal struggle, since it was a change in legal, external status [see Author’s Note 2]

But words, images, and names matter. Justification is an important metaphor or image to describe the reality and results of Christ’s work. So is “dying to sin” and being “buried with him by baptism into death.” Many associate Romans 6 with the idea of “sanctification,” or “making holy.” It certainly seems that Paul is moving in this direction by saying that we are no longer bound to sin now that we are bound to Christ. In being bound to Christ, we are allowed to participate in a new reality. [see Author’s Note 3]

But this reality is not simply a static position; it is a dynamic reality. In a sense, a whole new reality has opened up for us, but we have to live into it. Notice Paul’s words: “Therefore, do not let sin exercise dominion in your mortal bodies” (6:12) and “No longer present your members to sin as instruments of wickedness, but present yourselves to God as those who have been brought from death to life” (6:13); the italics I have added point out verbs that are in the imperative mood, one signifying commands.

In other words, we have some level of self-determinacy with regard to the role sin plays in our lives and the manner in which we present ourselves before God. We still can decide whom/what we worship in a post-conversion reality; it does not have to be hopeless and futile like it once was, but we are involved in the maturation and development of our salvation in some way.

God’s Grace and Our Response; Justification and Sanctification

Some traditions are really worried to say that we are involved in our salvation because they believe that this kind of reasoning takes away from the primacy of God. Although salvation is God’s and God’s to give, it is also true that part of us is involved in salvation; if it were otherwise, we would simply be automatons or robots in salvation. We are involved somehow in a responsive, secondary way to God’s initial grace but involved nevertheless. Without our responding, without our resisting sin and choosing to worship God every day, we would not have a dynamic relationship with God.

Paul continues in his logic by assuming that humans are constituted in such a way that we are naturally slaves to something — either to sin (and so the devil and/or ourselves) or to Christ. As theologians have repeatedly mentioned in antiquity, the chasm within the human self is so deep and wide that only God can fill it. [see Author’s Note 4] We were created for relationship, and when we seek to relate inordinately to that which cannot fill this chasm, we inevitably succumb to a disordered interior state. In repeating what has been said before in this Lectio series, we are what we worship.

“For just as you once presented your members as slaves to impurity and to greater and greater iniquity, so now present your members as slaves to righteousness for sanctification” (6:19). Names matter. We have not only been justified/reconciled to God through Christ Jesus. We have also died to sin — that is, we have been set apart for holy purposes. We have been joined to Christ, both in his death and in his resurrection.

In other words, we have been sanctified (made holy) and are in a continual, dynamic reality of sanctification in which our decisions and actions matter. We no longer have to be slaves to sin, but we can live into a reality of freedom, a freedom pivoting off of a condition of slavery to Christ. Justification and sanctification. Reconciled and made holy. Praise God for the various words we have to describe what Christ has done for us and in us. One word or metaphor cannot exhaust the eternal, beautiful, and utterly awe-inspiring love that God has demonstrated to us in the person of the Son, Jesus the Christ, the Messiah.

Questions for Further Reflection

- Many have observed that justification and sanctification are strong themes that emerge in Romans 5-6. How does the Lectio writer expound upon these two words as we wrestle with our identity in Christ?

- What do you observe in the text about how Paul references Adam? What connections does Paul make between Adam and Christ? What is the importance of this relationship?

- What imagery do you notice in chapter six? What do these word pictures communicate?

- The Lectio writer notes, “Because of Jesus, we no longer have to be enslaved to sin (6:6); rather, we have available to us a new way of life in which we can live in the power of the resurrection. What Paul is emphasizing is that we do not have to approach sin after conversion the way we approached sin before conversion. Something changes in us, in our status, and in our reality. In Christ, we are new creatures.” In what ways have you experienced this reality in your own life? What might it look like for you to embrace this new identity more completely?

<<Previos Lectio Back to Romans Next Lectio>>

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons License.