Jeremiah Week 3

Lament and Solidarity

Professor of Theology, Loyola University Maryland

Read this week’s Scripture: Jeremiah 7:1-10:25

17:07

Enlarge

Enlarge

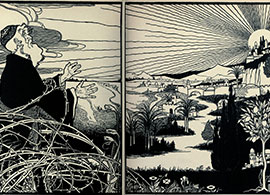

Lament and solidarity could be the title of many sections in Jeremiah, including this one. Lament is one of the ways we can address God when we sharply feel the great chasm between the way the world is and the way God wants the world to be. Think of how you felt when the police shootings of African-Americans in Baton Rouge and Minneapolis were followed by the shooting of the police guarding a protest in Dallas. Injustice piles upon injustice, leaving us grieving and longing for God’s redemption. In Jeremiah, Judah’s relationship with God has become corrupted. God is on the verge of punishing Judah, and Jeremiah cannot urge God to be unjust. In this position, Jeremiah does not wash his hands of these people. Instead, he grieves and laments.

A Call to Repent

This section begins as the word of the LORD again comes to Jeremiah. This time, he is told to deliver that word in the gates of the Temple in Jerusalem. This is the center of Israelite worship. Indeed, both God and the people speak of the Temple as the house of the LORD. If there is any particular place on earth where God might be thought to dwell, this is it. It becomes clear that the people badly misunderstand the nature of the claim that the Temple is God’s house. They seem to think that God would never willingly become homeless, never willingly abandon the Temple or let anyone else take it over. Moreover, they seem to think that they can rely on the Temple to be a place of safety for them under any and all circumstances.

Jeremiah’s oracle makes it very clear that this is not the case. The Temple may be God’s house, the dwelling of God, but unlike idols that require care and maintenance, the LORD does not need a house. God is not willing to overlook injustice in order to defend the Temple. The formula for remaining in the Temple, indeed for remaining in the land as a whole, is clear: repent. “If you really change your ways and your actions and deal with each other justly, if you do not oppress the foreigner, the fatherless or the widow and do not shed innocent blood in this place, and if you do not follow other gods to your own harm, then I will let you live in this place, in the land I gave your ancestors for ever and ever” (Jeremiah 7:5–7).

Although Jeremiah clearly articulates the practices that would demonstrate repentance, we have little reason to anticipate that the people of Judah will change. The reason? They do not recognize themselves in Jeremiah’s critique. Instead, they rely on the analyses of other prophets and priests who argue that there is nothing in Israel’s common life that would ultimately lead God to abandon the Temple. These words make it clear that Judah will not repent because the people do not recognize a need to repent. They do not seem to take the demise of Shiloh — the seat of the Levitical priesthood — and the collapse of Ephraim (the Northern Kingdom) as evidence that God will not overlook injustice (Jeremiah 7:12–15).

God Prohibits Jeremiah’s Intercession

At this point, the focus shifts from words of the LORD which Jeremiah delivers in public, to specific words from the LORD to Jeremiah. Jeremiah is told not to intercede for Jerusalem (Jeremiah 7:16; compare with Jeremiah 11:14). This raises an interesting set of theological issues. On the one hand, Jesus himself argues for repeated hopeful intercession in the parable of the widow and the unjust judge ( Luke 18:1–9). This reminds us that, as stated in the Book of Common Prayer, God’s “nature is always to have mercy.” On the other hand, Jeremiah cannot ask God to do something unjust. One can only invoke God’s merciful nature in the light of a prior plea for mercy. God’s command to stop intercessions for Jerusalem seems to be a recognition that the first step for the people of Judah in this situation is to recognize that the practices outlined in Jeremiah 7:5–7 truly characterize their society, that they are complicit in such practices, and that this fundamentally damages and endangers their life with God. Until the people of Judah come to recognize the truth about themselves, they will never throw themselves on God’s mercy.

To reinforce this judgment, the LORD details the process by which entire families become implicated in the worship of the “Queen of Heaven.” This is the goddess Ishtar who was associated with both war and fertility (Jeremiah 7:18–20). God reminds Jeremiah that such worship does not damage God. It hurts those caught up in such worship as it leads them ever deeper into God’s coming judgment.

Chapter 7 concludes a lengthy diagnosis that all of Judah’s troubles and all her sins stem from a disposition to disobey the Law. This failure of obedience is not new in Israel’s relationship with the LORD, but the people of Judah have taken it to new heights. God commands Jeremiah to continue to speak into the darkness of Judah’s disobedience, but offers no indication that the people will listen. Indeed, the opposite is true — the people of Judah have a deeply ingrained habit of ignoring the voice of God. They will not hear, and God will bring destruction. As chapter 8 begins, we see the interplay between announcements of specific judgments followed by repeated charges of unrighteousness and disobedience (Jeremiah 8:1–17).

Grief and Lament

Enlarge

Enlarge

In Jeremiah 7:16, God explicitly tells Jeremiah not to intercede for Judah. In Jeremiah 8:18–9:3, we find something resembling alternatives to intercession: grief and lament. When intercession has reached its endpoint, Jeremiah makes recourse to tears and mourning. It is exceedingly difficult to disentangle Jeremiah’s voice from the LORD’s voice in these verses. It may not be all that important to do so. Instead, in the light of God’s comprehensive indictment of Judah and promise of imminent judgment, we read an expression of profound grief from those who love Judah, whether God, Jeremiah, or both. Only deep love can account for the depth of this grief. There are not enough tears for the speaker to adequately respond to this situation (Jeremiah 9:1). It seems this grief is so sharp, its cause so lamentable, that God wishes to break away, to flee to the desert apart from Judah and her betrayals. As we have already seen in Jeremiah, the root cause of this betrayal is the supplanting of truth and fidelity with falsehood (Jeremiah 9:3).

In the subsequent verses, one sees the result of the victory of lies over truth. It tears apart the social fabric. Neighbors, relatives, anyone is now a potential enemy. No one is trustworthy (Jeremiah 9:4–9). In such a situation, one realizes how much of our social interactions, how many of our social institutions depend on an implicit level of trust between neighbors. Without this, social bonds break down and oppression flourishes. In poetic terms, Jeremiah presents the close connection between truthfulness, social cohesion, and social justice. Failures of truthfulness lead to breakdowns in community, which allow injustice to thrive. It seems relatively straightforward to transpose Jeremiah’s poetic observations onto the more prosaic admonitions of the letter of James. There, we find similar images of the power of the tongue ( James 3:1–12). Likewise, James is concerned with the social cohesion of the body of Christ and the prospects of oppression if believers do not attend to these matters with wisdom (James 2:1–8; 5:1–5). The same issues that lead to the demise of Judah’s social fabric work to undermine the common life of the church.

Returning to Jeremiah, we learn that the victory of falsehood over truth and fidelity in Judah incites a new round of grieving and lament (9:10–22). This culminates in a reassertion of those characteristics worthy and unworthy of boasting. Until recently, one might have said that in our culture, boasting was never seen as a good thing. In this, we are relatively unusual in human history. Most of the world’s cultures understood that there was a place for one to speak truthfully about one’s worthy achievements. Even in light of our recent politics, however, we can recognize with all ancient peoples that the key to appropriate boasting is to boast truthfully about what is worthy. Here in Jeremiah 9:23–24, the LORD offers a sharp distinction between those things that may appear worthy of boasting and those in which God truly takes delight: the knowledge of the LORD. More precisely, this means to know that the LORD is full of steadfast love, justice, and righteousness.

God and Idols

The first part of chapter 10 is one of the great satires of idol worship in the Old Testament. Already in Jeremiah, one has encountered the view that Judah’s idolatry is a form of betrayal like an adulterous affair in a marriage. Here we find another view of idolatry: it is an act of stupidity. The folly of idol worship is displayed by breaking down the steps involved in producing and worshipping idols. First, an idol begins as something living — a tree cut down, worked by an artisan, covered with silver or gold, and fastened in place. It is now thoroughly dead. It cannot move on its own; it has no living voice; it lacks power to do either good or ill (Jeremiah 10:3–5). Idols are purely the work of human hands. In contrast, the LORD is the living and true God. Rather than being made, this is the God who makes all things. This God has a voice that causes the earth to tremble. Ultimately, this God will bring judgment on all those who make idols and all those who worship them.

This approach to idols would lead to the view that there are no other gods but the LORD. Certainly there are a number of passages in the Old Testament that might lead one to think this (e.g. Deuteronomy 4:35 and 32:16–17, and much of Isaiah 40–66). Alternatively, there are passages which treat the LORD as the supreme God. This implies that there may well be other gods (e.g. Deuteronomy 4:7 and 10:17; Joshua 24). The Old Testament itself has little interest in resolving the question of the existence of other deities. Israel is called to love the LORD single-mindedly and wholeheartedly ( Deuteronomy 6:4–6). If this is the case, it really does not matter whether other gods exist or not.

Lament and Solidarity

Chapter 10 concludes with Jeremiah calling the people to prepare for flight and exile. As he anticipates life as an exile, Jeremiah turns to lament. The lament is very personal: “My tent is destroyed; my cords are broken; my children are no more” ( Jeremiah 10:20). This is Jeremiah’s pain rather than an expression of Judah’s pain. As his lament develops, he speaks of Judah’s devastation, too. Finally, the chapter concludes with Jeremiah’s two-fold prayer in verses 24–25. In the first part of the prayer, Jeremiah asks God to discipline him. This is not discipline as a form of punishment, delivered in anger. Rather, it is discipline in the sense of training. It is a plea to be formed and educated in God’s ways rather than to be subject to God’s anger. The prayer then turns as Jeremiah calls down God’s anger upon those nations who have wreaked destruction on Jacob and upon his fellow prophets who have misled the people. Interestingly, Jeremiah holds the deceitful prophets just as responsible for Judah’s demise as those nations who actually inflict God’s judgment on Judah.

Jeremiah contains two particular forms of address to God: intercession and lament. Both intercession and lament display Jeremiah’s deep compassion for the people of Judah and the depth of his relationship with God. Only one who loves the people of God and knows of God’s love for these people will feel compelled to intercede for them. It would be all too easy for Jeremiah to wash his hands of these folks and simply become the spokesperson for the LORD. That never happens. Throughout all of the suffering Jeremiah experiences in the course of his prophetic ministry, he never breaks with the people of Judah. Even when he is offered the opportunity to enjoy a life of privilege in Babylon (Jeremiah 40:1–6), Jeremiah chooses solidarity with his people among the ruins of Jerusalem. In addition to Jeremiah’s solidarity with the people of Judah, he also demonstrates the solidarity and fidelity to the LORD that enables lament. Jeremiah’s laments are inspired by the calamity facing Judah, but they are enabled by his confidence that God will hear him even as he cries out in pain. In these two respects, Jeremiah has much to teach Christians about aspects of prayer. Nevertheless, it is also clear that venturing into these realms of prayer also requires believers to enter into deeper levels of solidarity with the suffering people of God.

Questions for Further Discussion

- How do Jeremiah’s laments challenge you? How do they affect your understanding of prayer? Over what situations in the world do you lament?

- Idolatry is strongly condemned in this week’s reading. What forms of idolatry seem to be most tempting to the church today? How can believers resist these idols and obey the true God of Israel?

<<Previous Lectio Back to Jeremiah Next Lectio>>

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons License.