Romans Week 6

Law and Spirit: Romans 7–8

Seattle Pacific University Professor of Dogmatic and Constructive Theology

Read this week’s Scripture: Romans 7-8

13:48

Enlarge

Enlarge

It is part of human nature to resist when somebody says something can’t be done, right? Countless personal stories exist of people who defy the odds because they were motivated by people telling them they couldn’t do something. We value the courage and tenacity of those who beat the odds, who fight and eventually conquer and win.

Two Sides of Fortitude

It is a little different, though, when somebody is trying to help us by giving us advice, and we decide to go against that person’s advice simply because it is coming from somebody else. The advice may be wise and helpful, but something in us resists being told what to do.

It is fascinating in the continuum of life that sometimes those habits that make us who we are, that foster such wonderful things as strength and fortitude, may in other instances lead to stubbornness, pride, and maybe even our downfall. Being independent and stubborn can be both wonderful and terrible, depending, of course, on the advice in question and whether we discern it as being helpful or malicious.

When it comes to God’s self-revelation and all the forms it takes (e.g., commandments, narratives, oracles), we may find ourselves going against God simply because we don’t want to curb our desires or ambition. The law was meant to help us, to instruct us in the ways of righteousness, but living in a post-Fall world makes it hard to see the law as a sign of grace.

Rather, we tend to go our own way, to seek our own wills, to satisfy our own desires, and these often run contrary to God’s desires and plans — which are, if we trust and love God, for our benefit and good.

Flesh and Spirit in Romans 7

What Paul does in Chapter 7 is paint a picture of significant internal turmoil, one that often is labeled as the struggle between the flesh and the spirit. Reading Romans 7 it would be easy to forget that Paul is a Jewish Christian, for he spends quite a bit of time reflecting on how difficult the law has made our lives: how it is binding and how it arouses sinful passions. It takes us to task, telling us that we can never match up, because sin overpowers us and is all around us.

It almost sounds as if Paul is calling the law sinful — a deduction Paul is quick to dispel (7:7). From this discourse, many have assumed that the only value the law has is in exposing our sin to us, showing us our weakness, pointing us in turn to our need for the gospel. To a degree, this interpretation of Paul is accurate, but it is inadequate.

For Paul, the problematic issue is not the law; he mentions in this section that “the law is holy, and the commandment is holy and just and good” (7:12). The issue, rather, is with ourselves, particularly our sinful selves. We tend to live with a number of conflicting impulses, often stereotypically depicted in movies and cartoons by a nice, sweet angel on one of our shoulders and a sneaky-looking and good-for-nothing demon on the other.

It certainly is the case that we are driven by conflicting impulses before “we are in Christ Jesus” (8:1). One of the evidences of those who do not live in the Spirit is the degree to which they are deeply and utterly in a perpetual state of self-contradiction: “For I do not do what I want, but I do the very thing I hate” (7:15) [Author’s Note 1]. Often this state of self-contradiction is perpetuated and influenced by factors both within and outside ourselves. Whereas this is the state of folks who are not in Christ, I take it that Paul is saying that it does not have to be the state in which we live once we are bound to Jesus.

Sin’s Grip Loosened From Within

Let me explain. If we truly are dead to sin and alive in Christ, if we have been baptized into his death and raised in the power of his resurrection, then it makes no sense to say that we struggle with sin in the same way and to the same degree before and after coming to know Christ. All of us who are Christians struggle with post-baptismal, post-conversion sin. But I take it here that Paul wants to say that we are not doomed in this life to constantly be victims before the power of sin — in other words, that what we struggled with five years ago does not have to have the same grip on us today as it did then.

That is not to say that it will be easy. Overcoming sin is hard work, work that we can undertake only by the prompting, leading, and empowerment of the Holy Spirit. But, as we mentioned last time, Paul is providing a glimpse of a new way of life made possible by Christ. Something new has begun, both in ourselves and in the cosmos with the onset of the Christ-event. “For the law of the Spirit of life in Christ Jesus has set you free from the law of sin and of death” (8:2).

Amen! Hallelujah! What an amazing declaration! Paul continues with a strategy that is often overlooked here: However bad things are and have been, Paul makes it a point to say that they are and will be so much better now that we have Christ Jesus, “who in the likeness of sinful flesh … condemned sin in the flesh” (8:3).

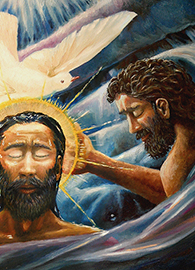

The amazing feature of the incarnation of the Son is that God has dealt with the human situation not from without but from within. Just as the ancients have said, God the Son became human so that we humans could become God-like [Author’s Note 2]. It is because God has dealt with sin and death that we can be righteous and alive.

And this reality ushered in by Christ is none other than to walk and live in the Spirit: “But you are not in the flesh; you are in the Spirit, since the Spirit of God dwells in you” (8:9). Again, Paul has in play here the issues of both a “state” and an “enactment.” To be in Christ means to be in the Spirit of Christ.

EnlargeThe Danger of “Christo-monism”

EnlargeThe Danger of “Christo-monism”

As a Pentecostal, I have been amazed to see how so many other Christian sub-traditions shy away from speaking of the Holy Spirit; often they revert to a Christo-monism in which God is thought of primarily in terms of Jesus. But Christo-monism has at least two very detrimental effects on the church. First, it has a way of reducing or overlooking the historical particularity of Jesus. Jesus was a man, who had a mom, and who had friends, most of whom betrayed or turned their backs on him. Yes, he was the Son of God, but he was also (and just as importantly) the Son of Man. He was a human, like you and me.

And second, in the absence of Christ’s bodily presence here and now, we have not been left alone but have another one like him, namely, the Spirit. Every person who believes in God, who cries, “Abba Father,” does so under the prompting and leading of the Holy Spirit. In this light, the Holy Spirit is not a special property of certain groups or churches. All who confess Jesus as Lord do so via the Spirit of God: “For all who are led by the Spirit of God are children of God” (8:14).

But this notion of being “in the Spirit” is both a state and an enactment: We are called to “put to death the deeds of the body” so that we may live (8:13). We are to call on God’s name, and the Spirit of God, the Spirit of Christ, will bear witness “with our spirit that we are children of God” (8:16) [Author’s Note 3].

The implications of being “in the Spirit” are cosmic in scale. Just as the creation is currently marked by all kinds of tragedies, calamities, and sufferings, so one day this same creation will be shrouded in and permeated by God’s glory. The great reversal of the work ushered in by the second Adam, Jesus Christ, will have effects not only upon humans and their conflicted state but upon the earth and its conflicted state: “For the creation waits with eager longing for the revealing of the children of God” (8:19).

What becomes increasingly clear through Paul’s ruminations is that being “in the Spirit” is a reality that is “already” unfolding but “not yet” fully realized. In many ways, this logic can be applied to a number of spiritual realities. We live in the “time between the times,” in between the initiation of the kingdom of God and its consummation, between the coming of the Messiah in all humility and comeliness, and his return with the heavenly host.

Being “in Christ”

We are caught up in a conflict now, but it is a different conflict from before. Before coming to Christ, we were caught in a crossfire that we could never win; we inevitably failed because our very selves were disordered on the way to death.

Being in Christ and in the Spirit means that we can live with the hope of victory, that death does not have the final word for the meaning of our existences, that we are on our way to see God. ”[T]he whole creation has been groaning in labor pains until now” (8:22). We are waiting, too. We see glimpses of that which is to come; we experience the first fruits of the Spirit; but we want more because we know in faith that there is more to come.

Yet we are held back to some degree by forces beyond our control. Barring Christ’s return in our lifetimes, we will all have to go through the valley of the shadow of death. We suffer. We hurt. We make mistakes and must live with their consequences. We wonder why we don’t see more of God in the world; we wonder where God is in a particular situation or moment.

Thankfully, we are not left alone; the Spirit who confirmed to us our adoption as daughters and sons of God also “helps us in our weakness” (8:26). Sometimes we don’t know what to pray or say, but those are not limits for the Spirit of God. The Spirit can and does break through all barriers — time, space, culture, gender, and even language.

There are no impediments in this life that can stand in the way of God’s fulfilling his promises to his people. It may not be evident to us at a given moment, but we are promised that “all things work together for good for those who love God, who are called according to his purpose” (8:28). Undoubtedly talking from experience, Paul can claim that nothing — neither “hardship, or distress, or persecution, or famine, or nakedness, or peril, or sword” — can separate us from the love of Christ (8:35). That is most certainly a blessed kind of assurance, a promise that we can take to the bank. Again, those things Paul mentions are not easy; in many cases they can lead to our deaths. But what is death to us who live in the Spirit, who are joined to the resurrected Jesus?

Questions for Further Reflection

- What things does Paul conclude about the role of the law in the life of a Christian? How should we relate to the OT law as people who live in light of Christ?

- What specific themes or ideas does Paul draw out about life in the Spirit? Spend some time reflecting on these specifics in the context of your day-to-day discipleship.

- What do these two chapters tell us about the “now” and the “not yet” aspects of living as a Christian? Describe some of the ways that you have experienced this tension.

- These chapters seem to be full of contradictions as Paul works through the tension of the flesh and the spirit. What word of hope does Paul (and the Lectio writer) ultimately provide as we struggle with sin?

<<Previos Lectio Back to Romans Next Lectio>>

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons License.