Joshua/Judges Week 7

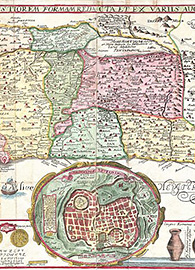

Location, Location, Location!: Joshua 13:1-24:33

Assistant Professor of New Testament, George Fox University

Read this week’s Scripture: Joshua 13:1–24:33

16:55

EnlargeIntroduction

EnlargeIntroduction

About seven chapters of the latter part of the book of Joshua detail the distribution of the land of Canaan to the tribes of Israel. You will not hear many riveting sermons on these chapters or read gripping theological books based on them. Like the Gospel genealogies, most readers (including myself!) would have a tendency to glide right through them, skimming for any possible “bit” of interesting information.

But even though the events of these chapters might mean relatively little to us today, they were momentous for Israel. I am reminded of the movie Castaway, where the corporate FedEx plane of Chuck Noland (Tom Hanks) crashes and he is stranded on a deserted island for four years. When he is finally rescued, can you imagine what it would feel like to have a house? A refrigerator? A mailbox?

Imagine how many days and nights on that island he dreamed of ice cream cones, a hot shower, even just a pillow or a fork!

I would imagine that the Israelites, after years and years of slavery in Egypt and wandering in the desert, would have felt a sense of deep fulfillment as they received their allotment of land — the confirming sign of God’s rescue mission seeing its completion (until we get to Judges!).

God Almighty and Israel “Almost”-y

When reading the first dozen or so chapters of the book of Joshua, there is a sense in which things wrap up rather neatly. This comes out especially in Chapter 11:

As the LORD had commanded his servant Moses, so Moses commanded Joshua, and so Joshua did; he left nothing undone of all that the LORD had commanded Moses. So Joshua took all that land … all were taken in battle …. And the land had rest from war (11:15–23).

Yup. That sounds pretty final. YHWH is in charge, not the Canaanites. He defeated them without breaking a sweat.

Then we get to the chapters pertaining to the allotment of the land (especially Chapters 13–19) and we see this pattern:

- “[T]he Israelites did not drive out the Geshurites or the Maacathites” (13:13).

- “But the people of Judah could not drive out the Jebusites [so they] live with the people of Judah in Jerusalem to this day” (15:63).

- “They did not … drive out the Canaanites who lived in Gezer” (16:10; see also 17:12–13).

Certainly we could say the earlier statements about complete victory made in Chapter 11 were a bit of an exaggeration, but what benefit would there be to saying the Israelites had succeeded so comprehensively if they actually hadn’t?

The book of Joshua sustains a key tension that appears throughout the entire Old Testament. On the one hand, God made promises that he intended to keep — to free, teach, preserve, and bless Israel. The language of victory, then, I believe underscores the trustworthiness and power of YHWH on behalf of his people. He is Almighty.

On the other hand, contrasting with the “all-might” of YHWH is the “al-most” of Israel — “almost” able to get it right, “almost” wholly possessing the land, “almost” trusting fully in their God. Nevertheless, the distribution of the land is an opportunity to have faith in the God who has given over the whole territory into their hands even though some Canaanites remain. What will they do?

The Good

Right away we have an example of fidelity, strength, and courage in the territorial acquisition of the tribe of Judah. Within that tribe is Caleb — an elderly man from the wilderness generation who 45 years earlier was sent along with Joshua to spy out the land (Numbers 13–14). Fearlessly taking on the “three sons of Anak” and the people of Debir (Joshua 15:14–15), Caleb showed great loyalty to YHWH’s promise and protection.

In the wilderness time, the Lord saw in Caleb a “different spirit” as one who followed him “wholeheartedly” (Numbers 14:24). In spite of knowing that the land he was to inherit had “great fortified cities,” he believed that “the LORD will be with me, and I shall drive them out, as the LORD said” (Joshua 14:12). He is a model for the Israelites. (And apparently in the books of Joshua and Judges good models are a rarity.)

The Bad

Caleb requested a special territory to occupy, but that was the exception, not the norm. Most of the tribes received their allotment by the casting of lots (similar to the rolling of dice). The tribe of Joseph was unsatisfied with its lot (17:14–18), complaining both about the small size of it and fearing the might of the Canaanites in the land who have “chariots of iron” (17:16). Despite all that YHWH had done to demonstrate his going before and being with his people (as Caleb did recognize), the Josephites were reluctant to lay claim to this hope.

The Ugly

According to Numbers 32:1–5, while Israel was journeying towards the land of Canaan (prior to the events of the book of Joshua), the tribes of Reuben and Gad, and the “half-tribe” of Manasseh, requested to settle in the land east of the Jordan (called the “Transjordan”). Moses’ response to this expressed a concern that these tribes, who were looking for a lush and fertile area of land (32:4), would be abandoning the work of the imminent military campaign the rest of the Israelites were going to engage in “across the Jordan” (32:5).

Eventually, they came to an agreement — these tribal soldiers would fight with Israel until the land was conquered; then they would return back to the Transjordan, where their families were settling. While Joshua blessed these two-and-a-half tribes for fulfilling their obligation (Joshua 22:1–6), there was still a sense in which they were frustrating the unity of the whole people of Israel by choosing to settle so far from the remainder of the tribes.

Moses had already seen in these tribes a propensity towards weakness and sinfulness. Their reluctance to enter the Promised Land would certainly cause other Israelites to re-think the whole plan. Fortunately, as we know from the book of Joshua, the worst-case scenario did not happen. The remaining tribes stayed together.

However, in Joshua 22:10–34 we do find a signal that this set-apart, Transjordan contingency was making trouble. Probably with the best of intentions, they built a large religious altar. The “rest of Israel” mistook this for a pagan altar and took up arms, ready to slaughter the apostate tribes.

Ultimately the confusion was cleared up — the altar was meant to be a memorial to YHWH. Thank goodness no blood was shed over this misunderstanding. However, this episode demonstrated the disunity of the people. Because they lived “on the other side of the tracks,” so to speak, the Transjordan tribes wanted to feel that they too worshipped YHWH, even though they did not live near Shiloh (the makeshift “center” of the LORD’s presence). The scene ends in peace as tribes from both sides of the Jordan recommit their bond to each other under YHWH, but the distance is not thereby completely bridged.

God of Promise and Justice

What can we make of “The Good, The Bad, and The Ugly” in these chapters? One clear thematic impulse is that YHWH is reliable. He makes promises (all the way back in Genesis 15:7; compare Genesis 12:1) and keeps them. He says, “Don’t worry about obstacles like people and disasters and your own physical limitations — I will be with you and I will take care of you.” If ever there was a time for an “I told you so,” the end of Joshua would be it.

A second key point involves the “ways” of YHWH. While we may struggle over issues of God’s people killing and making war, the land-allotment chapters clearly reveal a God who cares about equity and justice. Two examples demonstrate this clearly:

- First, as briefly mentioned above, the properties were distributed by the casting of lots. While this may seem like leaving it to chance, Israel would have recognized this as leaving the decision in God’s hands: “The lot is cast into the lap, but the decision is the LORD’s alone” (Proverbs 16:33). Even if one is not to imagine God turning the sides of the dice himself, we can still appreciate that this method would have eliminated temptations to make the strong or wealthy even more prosperous and the needy more in need.

- Second, we see the concern for justice in the assigning of cities of refuge (Joshua 20): marked off territory where someone accused of murder could flee until a trial was held (or the current high priest died) (20:1–6). The point was not to let murders live in peace, but to give sufficient safety from an avenger until the matter could be settled and guilt proven.

Furthermore, such a provision was extended not only to Israelites, but also to any foreigners living among them. (This gave me pause to think about how “foreigners” are treated in my own country and whether or not they are given appropriate hearings and rights.)

Whose Land Is It Today?

Before concluding a discussion of the book of Joshua and moving on to the time of the Judges over Israel, the question might linger: “Whose land is it today?” Clearly, according to the Old Testament, God called Abraham, made a covenant of promise with him, raised up great leaders from his children, freed his people from bondage in Egypt, led them personally in the wilderness, and gave them Torah (his guiding law) — largely with a view toward fulfilling his promise to make them a great people in a special land. That is what we mean when we call it the Holy Land.

But we know now that there is much conflict over this portion of earth. Who lays proper claim to it? Put more directly, should Christians around the world lobby (and pray) for the eventual full possession of this land by the nation Israel?

Many Christians believe so. Jerry Falwell once claimed that America is blessed by God because her leaders have felt it right to support Israel. The interest in helping Israel to fully recover its land-property comes from a particular reading of the Old Testament (and especially a book like Joshua) with the assumption that the Promised Land is and must always be Israel’s land. The Christian encouragement to support Israel is also often fueled by discrimination against Palestinians as Islamic idolaters.

What should we make of this in light of what the Christian Scriptures, Old and New Testaments, teach?

- First, we should not confuse Canaanites and Palestinians. The Canaanites were not inheritors of the promise of Abraham. However, Arabs are technically children of Abraham (through Ishmael). Should we treat modern Arab Palestinians as Canaanites who need to be removed, even though they share “Father Abraham”?

- Second, and more importantly, I want to make the point that Scripture must be read as progressive revelation — just because an important promise, idea, or principle was stated in the Old Testament doesn’t mean that it has complete application or validity for today. For example, in the OT, Jews were not allowed to eat certain kinds of food. Daniel is praised for showing such piety in this regard (Daniel 1:12–21). However, in the New Testament we are shown that Peter is given a special vision where he is told to “kill and eat” animals he was not permitted to eat according to Old Testament law (Acts 10; compare Mark 7:19).

This was a symbol of a new phase of God’s history, where any food could be eaten; but the wider point of the vision was that Gentiles could be accepted “as is,” as long as they embraced Christ — they did not need to follow the rituals of the Old Testament law.

Another example, a bit closer to home in the book of Joshua, is the matter of “rest.” Finally we are told that the LORD gave Israel her long-awaited “rest” (23:1). In the book of Hebrews (in the New Testament), we are told, No, Joshua did not lead them into God’s rest — the great “rest” is still waiting for us in the future (Hebrews 4:8–9)

So how do we know whether to see the land-fulfillment in the Old Testament as temporary or eternal? One clue is to notice that “land” plays almost no role in the New Testament — at least the particular land of Israel plays little to no role except as the hub of activity for the life of Jesus. We see the importance of “land” overall in books like Luke and Acts (which was written by Luke). In Luke, Jesus moves toward the center of Israel, Jerusalem, until he is finally crucified there and rises again.

In Acts, the movement is in the opposite direction, initially in Jerusalem and then outward to the furthest regions. The life of Israel was coming to a head with Jesus, so the Gospel of Luke is somewhat centripetal — pushing Jesus to the heart of Israel only to be destroyed there. In his “new life,” he brings the light of God outward, centrifugally, to the whole world. Hence the Lord’s Prayer: “Your kingdom come. Your will be done, on earth as it is in heaven” (Matthew 6:10).

Finally, I wish to reiterate the important point that the ethical framework of the Bible, and especially the New Testament, is not about God’s supporting a particular ethnic or political people. Even with the Israelites, they were permitted to maintain possession of the land and inheritance of it only if they remained faithful to YHWH — thus Achan was “Canaanized” for his disobedience, while Rahab was accepted for her faith in Israel’s God.

Caleb, one of the great heroes of the book of Joshua, is called a “Kenizzite,” which means that he was probably originally an Edomite, a descendent of Esau’s grandson Kenaz, and, thus, not purely an “Israelite” (because he was not descended directly from Esau’s brother, Jacob, who is also called Israel).

I believe that the “Christian” responsibilities in the current Israeli-Palestinian conflict are these:

- To know as many of the facts, and as much of the history and “messy politics,” of the situation as possible before making judgments,

- To seek out fair treatment and the supporting of basic needs for all parties involved, and

- To show the love of Christ in service and self-sacrifice.

From Joshua to Judges

Joshua, with all of its ups and downs, ends on a high point of “rest” and fulfillment of God’s promise of freedom and land. Things don’t stay peaceful and quiet for long, though. The book of Judges brings a new host of problems and failures. Israel’s journey is far from over. It has only begun.

Questions for Further Reflection

- Chapters 13-21 of Joshua are often skimmed by readers. What does the Lectio writer say about the importance of these texts?

- Have you ever had the experience of having your own “place” (dorm room, apartment, house, etc.)? What did that feel like? Knowing the whole of Israel’s story (Abraham’s calling, enslavement in Egypt, God’s dramatic redemption, and their 40 years in the wilderness), reflect on some of the thoughts and feelings the people might have been experiencing.

- The primary method for dividing the land of Canaan among the Israelites was by “casting lots” – like rolling dice. Was this a good strategy? Why or why not? What does the Lectio writer say is demonstrated about God’s character through this process versus having a leader divvy up the land?

- What is the responsibility of Christian churches in regard to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict today? Should Christians get involved? Why? How much and in what ways? How does Scripture inform our choices?

<<Previous Lectio Back to Joshua/Judges Next Lectio>>

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons License.

Thank you, Dr. Gupta, for your insight into the book of Joshua. I am excited to read Judges along with you as well!

I completely agree but I’m just curious, a point to ponder not a point of contention but wasn’t there some strife that was cursed or foretold on/about ishmael and his nation? Also does any of Revelation discuss the possibility that the possession of Israel as part of a sign of approaching end?