Hebrews Week 6

Practice Perfection: Hebrews 5:11–6:20

By Rob Wall

Paul T. Walls Professor of Scripture and Wesleyan Studies

Read this week’s Scripture: Hebrews 5:11–6:20

22:09

Enlarge

Enlarge

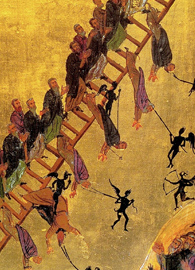

Even though no stats are kept about such things, it could be argued that this passage is the letter’s most discussed and debated. Not only is Wesley’s controversial teaching about Christian perfection anchored by the Preacher’s charge, “let us go on to perfection” (6:1, Wesley’s translation), it also includes the sharp warning that Christians who have experienced God’s saving grace, only then to give up on Christ, will never again be restored to God’s eternal embrace (cf. 6:4–6).

The very idea that the believer could possibly lose her residence in God’s household — that anything we do is greater than the grace God gives — is offensive to some Christians. However we interpret this hard text, it teaches us that thoughtful Christians who bet on eternal life cannot be nonchalant about their future destiny, as though God does all of salvation’s heavy lifting. They understand what’s at stake and therefore place considerable weight on how to get there. The prospect of not entering into God’s promised rest because of spiritual failure or theological immaturity is deeply troubling to those who expect it.

Cooperative Covenant-Keeping

Perhaps now is a good time to remind us that this letter’s title, “To the Hebrews,” recalls the biblical story of God’s liberation of the Hebrews — God’s chosen people — from captivity. On the one hand, their deliverance from suffering testifies to God’s faithfulness to promises made: God never undoes the election of Israel. The Church doesn’t replace Israel, as if God had negated Israel’s chosenness because of Christ. Rather, Christ’s followers are “grafted into” Israel (Romans 11:16–24; cf. Isaiah 5:1–7) to create “God’s Israel” (Galatians 6:16) [see Author’s Note 1].

On the other hand, the unfaithfulness of the exodus generation in the wilderness lost them entrance into their promised future. The Preacher’s severe warning puts in bold relief what Wesley (following Scripture’s lead) teaches about the nature of God’s saving grace and the covenant relationship into which grace initiates the believer: covenant-keeping is cooperative.

Yes, God initiates salvation by acts of unconditional, unmerited love with the promise to maintain Israel’s salvation from beginning to end. Salvation is God’s alone to offer and to secure. Nonetheless, God doesn’t force salvation down our throats; it is a gift freely given that transforms our lives only when we freely receive it, by an act that St. Paul calls “the obedience of faith” (Romans 1:5; 16:26; NRSV). No matter how majestic this belief is, the operations of God’s grace remain a bone of contention among Christians.

A Warning to Sluggish Students!

But this passage is important for still another reason. It makes clear the real crisis that threatens a people’s forward journey to the Promised Land. Notice that this week’s passage is bracketed by the Preacher’s repeated rebuke that his readers are “lazy” (nōthros; Hebrews 5:11; 6:12), a Greek word that identifies people who lack a work ethic. Rabbi Philo compared lazy students to statues with fabricated ears that can’t hear a thing and therefore can’t learn what is taught to them. The warning about the prospect of a lost salvation (6:4–6) or even the famous exhortation to “go on to perfection” (6:1) may be rhetorically charged to wake up sluggish students!

More critically, the Preacher’s purpose in writing his “word of exhortation” (13:22; NRSV) is not to bludgeon his readers with uncompromising threats or impossible demands. He rather seeks to awaken them from intellectual slumber to a life of intellectual renewal (cf. Romans 12:1–2) that concentrates on learning about God’s Son, which prepares them for the wilderness journey ahead.

A Solid-Food Catechesis

In fact, the central concern of Hebrews is catechesis — orderly theological instruction that targets a learning outcome (in this case, a “perfect” or complete understanding of Christ; cf. 6:1). This concern is cued by the Preacher’s obscure claim that Jesus is a “high priest according to the order of Melchizedek” (5:10). What significance is there in identifying Jesus with a passing character in Scripture’s ancestral narrative? Even the Preacher knows that this claim, his sermon’s pivot point, is difficult to understand and requires explanation (5:11). More on this later.

Appropriately, then, the congregation of readers is urged to practice a catechesis of “solid food” that will clarify the revelation of God’s “word of righteousness” in Christ (5:12–14; cf. 6:3). Any parent understands the Preacher’s use of the milk/solid food metaphor. Infants are fed milk until their digestive systems develop the capacity to break down and absorb the nutrients of solid food, which are needed to grow to adulthood. Lazy learners are unprepared to receive the nutrients of God’s Word (5:11; 6:12), without which their spiritual growth is impossible and spiritual failure will likely result (cf. 3:18–19; 4:11–13).

The Preacher’s congregation (which includes most of us) has already learned “the introduction to the basics about God’s message” from the apostles (cf. 2:3–4). They’ve finished the required course work, which is necessary but still insufficient to “perfect” a holy people (6:1) destined to inherit God’s promises (6:12). New converts know from day one that “dead works” are sinful, “faith in God” is necessary, worship is important, and Christian hope for “resurrection from the dead” is non-negotiable to sustain Christian discipleship (6:1–2). These are the real fundamentals of the faith. But still more learning about Jesus is needed to complete their theological education.

Perfect Understanding

The “therefore” of Hebrews 6:1 (NRSV) draws the Preacher’s conclusion from his handwringing of 5:11–14. The shift from the verbal form of perfection, “being made perfect,” to its nominative form, “perfection” (NRSV), suggests that a fixed or stable state of Christian existence is under discussion. Up to this point Hebrews has used the verb “to make perfect” to characterize the Lord’s learning process in being faithful. Jesus learns from a catechism of suffering and spiritual testing, completed at His exaltation, in order to become our sanctifying sanctifier (2:11).

The skillset acquired through the process of being made perfect enables Jesus’s pastoral care and priestly mediation for a people who struggles and strives every day to obey God’s Word. While the Preacher’s exhortation, “go on to perfection” (6:1), assumes the dynamic quality of a process, his use of the noun, “perfection,” focuses readers on the final product (6:12). That is, a “perfect” or complete understanding of Christ, the goal of spiritually lazy readers, is presently incomplete. They are just not ready for primetime, and the prospect of spiritual failure is more likely.

Few scholars read Hebrews 6:3 as anything more than a “pious aside” without any importance to the Preacher’s exhortation. In context, however, this verse sounds his pledge to pastor his readers in a process of learning — again, a Christological catechism — whose holy end is to form a deeper understanding of the risen Lord. The modest refrain “if God allows” (6:3) may simply admit that grace does not happen in a vacuum or without our permission and cooperation.

Those Who Fall Away

The Preacher’s use of catechism as a pattern of theological formation frames one of the letter’s most evocative warnings: that God will not restore the salvation of a backslider (6:4–8; cf. 10:26–31; 12:15–17). The assumption, of course, is that by completing rigorous instruction the congregation of readers will never give up on Jesus. Apostasy (i.e., a denial of the apostolic witness of Christ; cf. 2:3) is a real possibility only for the intellectually lazy. In this sense, then, the warning is not about a God who is unwilling to forgive and to restore the spiritual fortunes of the repentant. The warning is about Christians whose failure to participate in a rigorous round of theological education makes it impossible for them to turn back to God. The reference to the practice of distinguishing between good and evil (5:14) provides the pivot for this entire passage since it highlights the skill honed by catechism: the critical capacity to discern good theology from bad theology. Such a competence would make apostasy impossible.

The congregation’s experiences of the Holy Spirit’s baptism, vividly noted by the sensual images of “see[ing] the light” and “tast[ing] the heavenly gift” (6:4), recall the similar experiences catalogued in Hebrews 2:4 that accompany the apostolic proclamation of Jesus (2:2–3). Both kinds of experiences, charismatic and ordinary, confirm that the congregation has already received God’s saving Word through the apostolic witness of Jesus, the subject matter of a catechism that perfectly forms the faithfulness of Christians.

Against this backdrop, then, the prospect of apostate Christians who “turn away” (6:4) from Christ is rooted in their lack of theological understanding, if not also their amnesia of those experiences of its eternal truth. The irony is expressed as a tragic reversal: in rejecting the exalted Son whose death results in these grand experiences of salvation, apostates join those who “crucify[…] God’s Son” by “exposing him to public shame” (6:6). The Greek word translated “public shame” alludes to the crucifixion. This allusion to the brutal spectacle that took place prior to Roman executions to shame the criminal is used here of the spectacle that takes place after Jesus’s death to shame his followers. The stunning substitution of “God’s Son” for Jesus in the phrase “crucify God’s Son” only intensifies the disgrace [see Author’s Note 2].

Check out social media. Those who ridicule the Christian faith in blogs or on Facebook often appeal to the testimonies of ex-Christians for support. Consider also the portraits of lapsed believers in film who are used to illustrate an outlook on life contrary to Christ. In my experience, the lurid testimony of apostates (along with the hypocrisy of confessing Christians) is far more damaging to God’s reputation than the most sophisticated arguments of atheists.

Enlarge

Enlarge

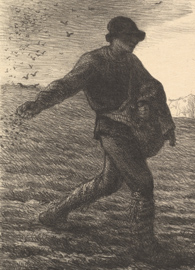

The well-used biblical image of two kinds of soil recalls the distinction made earlier between “good and evil” in 5:14. Christian catechism cultivates the farmer’s skill at distinguishing between different soils in which the planted seed (i.e., God’s Word; Luke 8:4–15) either flourishes or doesn’t. In this context the ground that “drinks up the rain” (Hebrews 6:7) alludes to the Promised Land (Deuteronomy 11:11), while the cursed ground that “produces thorns and thistles” (Hebrews 6:8) alludes to fallen Eden (Genesis 3:17–18). Not only is the apostate prevented from entering the Promised Land, but the reversal of faith results in a reversal of religious experience since the powers of new creation retreat back into fallen Eden. Clearly the fiery future of that pile of thorns and thistles culled from contaminated land evokes images of God’s final judgment (cf. Hebrews 12:29; Revelation 20:14).

Participating in the Kingdom Community

The Preacher doesn’t linger long on this disturbing idea. The call to “go on to perfection” (6:1) is a pastor’s positive exhortation to take seriously “the pedagogy of the Spirit” (Origen) when God’s Word is studied in the presence of God’s Spirit to prepare Spirit-led believers for their long obedience toward the heavenly Jerusalem (cf. Hebrews 12:23). For this reason, the Preacher addresses readers as “brothers and sisters” (6:9). The CEB’s translation obscures the intimacy of his address: the Greek word is better translated as “loved ones” (agapētoi).

Not only does the Preacher express confidence in their favorable response, but his confidence is grounded in the “better [or superior] things […] that go together with salvation” (6:9). Comparisons of superior things for our salvation pepper this letter. They mostly have to do with Christ’s exalted status or effective work, but also imply the superior results that benefit those who trust in God’s saving Word. The implicit source of the Preacher’s confidence, then, is the persuasiveness of his argument for Christ, but also the believer’s participation in the kingdom that follows from it.

Careful readers will recognize St. Paul’s familiar triad of Christian virtues that characterize those who obey God’s Word: faith (6:12), hope (6:11), and love (6:10). The community’s cultivation of these virtues through worship practices (singing, sacraments, Scripture reading, prayers) and Christian fellowship is every bit as important as the catechism that initiates believers into the “solid food” of God’s Word. Both are necessary components of a fully formed Christian community that learns to love and obey God perfectly.

Motivating such a community’s obedience is that God is fair-minded. God gives gifts, but God also rewards good work (cf. James 1:17). We should assume both gift and reward are flipsides of God’s grace. In this sense, the Preacher recognizes that perfection is impossible without believers’ faithful service to God — by God’s grace — which results in reward (Hebrews 6:10). We are not told the nature of this reward, but it doubtless in some sense assures the community’s future participation in the kingdom. Hence good work “make[s] your hope sure until the end” (6:11; cf. 1 John 4:7–18).

Role Models of Faith

The idea of imitation is thematic of Scripture’s teaching of Christian community. Every congregation needs exemplars of “faith and patience” (6:12). We should identify them as our spiritual leaders and teachers. Ideally, their mature understanding of the gospel is embodied in the manner of their holy lives. In my life, my parents and my wife, Carla, have provided this example. The memory of my beloved seminary professor, Harold Hoehner, does as well. You have your own examples, too. Hebrews 11 provides a goodly list of biblical exemplars whose faith in God is embodied in their faithful lives (wait for Lectio 10!).

Lazy learners ignore possible role models in their own community — those whose “faith and patience” forge the faith of those who “inherit the promises” of God (6:12). Lazy learners go it alone in the wilderness without complete understanding of Christ, without the help of God’s sanctifying grace, and without the guidance and support of the community of faithfulness. They are the most at risk of spiritual failure, and they are targeted by a caring Preacher’s exhortation to go on to perfection.

Even though he is warning the spiritually apathetic, the Preacher expresses confidence that his readers know heaven is at stake, and that they are motivated to press on to the end. But recognizing the fragile nature of their “faith and patience,” he assures them that God’s inviolate promises, which map their journey into salvation’s future, are secured with a “solemn pledge” (6:12–20; cf. 7:20–24).

A God Who Keeps Promises

Common sense teaches us that the agreements we enter into, whether contractual or verbal, are only as good as the integrity of the parties making them. Professional athletes who refuse to play unless owners tear up an existing contract and pay them what they are worth lose credibility in the eyes of fans. God’s oath-making reflects God’s character. Because God does not lie (6:18), the promise made to Abraham and Sarah is fulfilled in the exodus. The curious phrase “swore by himself” (6:13) recalls the final iteration of God’s promise of a great nation, made under oath in response to Abraham’s willingness to sacrifice his son Isaac (Genesis 22:16–17; cf. Hebrews 11:17–19).

In this way, Abraham’s act of obedience to God provides an example of “faith and patience” (6:12) for all Christians who “have taken refuge in him” (6:18) — that is, in the promise God made to Abraham that “all the families of the earth will be blessed because of you” (Genesis 12:3). That promise of divine blessing, made to Abraham under oath by a God who does not lie, is the metric of a people’s hope — the “secure anchor for our whole being” (Hebrews 6:19) — and it motivates our movement toward heaven.

A smart man once told me that religion is only as good as what it hopes for. The Preacher would agree, but would add that religion’s hope is only as good as the God who promises it and the “pioneer” who leads us there (2:10). A promise-making God whose faithfulness never falters and whose truth-telling never wavers guarantees our inheritance. The exalted Son who knows the way and has already entered heaven has done so “for us” (6:20). Jesus continues to provide pastoral care and accurate directions during our wilderness sojourn as our “high priest according to the order of Melchizedek” (6:20). The practical importance of the Preacher’s claim is developed over the next several chapters of his letter to us.

Questions for Further Discussion

- Wall says that “covenant-keeping is cooperative,” implying that we have a say in our own salvation. What did your tradition teach you about your role in your salvation? Do you think salvation can be lost? (Dr. Wall calls this issue a “bone of contention,” so expect disagreement!)

- How does Dr. Wall define “perfection,” according to 6:1? If Christians are to “go on to perfection,” what are some practical ways one might go about doing that?

- What kinds of spiritual practices, church traditions, or activities fall into the category of “mother’s milk” according to the Preacher? What would fall into the category of “solid food”? Take an inventory of the activities in your church congregation; how would you categorize them in these terms? What might you suggest adding into/removing from the life of your church?

<<Previous Lectio Back to Hebrews Next Lectio>>

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons License.