John Week 2

Show and Tell: Testifying to Jesus: John 1:19–51

Seattle Pacific University Assistant Professor of New Testament

Read this week’s Scripture: John 1:19–51

13:11

Key Prologue Terms: revelation, testimony, rejection

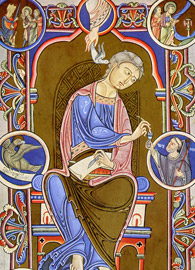

Enlarge

Enlarge

Aspiring writers are often advised, “Show, don’t tell. Take readers along for the journey; don’t narrate events at a distance.” If this had been the writing advice in the first century, the fourth evangelist would have failed miserably. John’s gospel repeatedly tells readers what has already happened rather than showing them the events along the way. However, by doing this John is able to indicate not only the events that happened but also their significance.

As we saw in Lectio 1, the prologue (John 1:1–18) brings the reader along to poetic heights, exalting Jesus as God’s equal as well as one who is “among us” (1:1, 14). Yet, the gospel begins on earth simply with the “testimony given by John” (1:19). This John is the one who is baptizing in the wilderness (1:23, 25; cf. 1:6–8, 15). He introduces us not only to Jesus but also to one of the most pervasive themes of the fourth gospel: characters in this gospel “testify” or “bear witness to” who Jesus is. This testimony enables faith to grow until others are able to encounter Jesus themselves. The focus of the remainder of John 1 is on testifying to Jesus’ identity and mission.

The evangelist has structured John 1:19–51 carefully, noting both the characters involved in each scene as well as the passage of time. We read about four consecutive days in these passages, and each day involves one of the two primary characters from the previous day. In this way the days are chain-linked together, providing a sense of both forward motion and continuity. On the first day, we see John the Baptist as he encounters some Jews (1:19–28). On the second day, we meet John the Baptist and Jesus, but John is the focal character (1:29–34). On the third day, John fades into the background, and the spotlight is on Jesus and his first disciples, Andrew and Simon Peter (1:35–42). On the fourth and final day, we meet Jesus and two other disciples, Philip and Nathanael (1:43–51). The emphasis of each of these early sections is on the testimony of others — John the Baptist, Andrew and Peter, Philip and Nathanael — and how they bear witness to Jesus.

Day One: John’s Testimony: It’s Not About Me (1:19–28)

When we first encounter John in this gospel, he is testifying to priests and Levites who have come from Jerusalem. First they ask John about his identity: “Who are you?” (1:19), and then they ask him about his mission: “Why then are you baptizing?” (1:25). John redirects their questions to focus on Jesus rather than on himself. This is the repeated pattern of testimony in this gospel. It always takes the focus off the one who is testifying and puts the center of attention back on the identity and mission of Jesus.

In answering the question about his identity, John “confessed and did not deny it, but confessed, ‘I am not the Messiah’” (1:20). This language implies that there were some who did believe that John was the promised Messiah, and therefore he must clear up this confusion (see also Luke 3:15). The priests and Levites wonder if he is Elijah (see Malachi 4:5) or “the prophet,” meaning the promised prophet like Moses (see Deuteronomy 18:15) who was to come in the last days. These questions highlight the confusion surrounding John’s identity and testimony. The gospel’s readers have an advantage over John the Baptist’s audience: we know the prologue (1:1–18). [Author’s Note 1]

When these priests and Levites ask John about his mission, they ask him why he is baptizing if he is not one of these promised figures. As in the other canonical gospels, John quotes from Isaiah 40:3 (John 1:23); however, John does not claim that he is preparing the way for Jesus. Instead he again shifts the focus back to Jesus: John’s role is to reveal Jesus to Israel (see 1:31). In this passage the revelation is cryptic and puzzling. Jesus is the one who is “among you” and yet “you do not know” him (1:26). These phrases echo the prologue’s testimony. The Word has become flesh and is dwelling “among us,” but Jesus “was in the world […] yet the world did not know him” (1:14, 10). Throughout the gospel Jesus’ revelation will be apparently clear to readers, and yet his audience often does not understand. John’s testimony yields a similar response.

Day Two: John’s Testimony: The Lamb of God (1:29–34)

Enlarge

Enlarge

When John sees Jesus the next day, he points to him and declares, “Here is the Lamb of God who takes away the sin of the world!” (1:29). This startling statement is notable for several reasons. Among the gospels, only John calls Jesus “the Lamb of God” (cf. Revelation 5:6; 7:17; 17:14). Lambs were not used regularly for sin or purification offerings; bulls and goats were much more common (though see Leviticus 4:32). In the Temple lambs were to be sacrificed twice daily (Exodus 29:38–46), but not for the forgiveness of sins. So it is unclear what John the Baptist means when he calls Jesus “the Lamb of God” if the Lamb’s primary task is taking away the sin of the world. However, the title echoes several contexts in the Old Testament, from Isaiah’s Suffering Servant (Isaiah 52:13–53:12) to Passover. In each of these contexts the lamb either takes on the sin and brokenness of the world (Isaiah) or delivers Israel from sin and oppression (Passover; Exodus 12; cf. 1 John 2:2). Just as God loves the whole world (John 3:16), so the Lamb of God provides a means of deliverance for the whole world (1:29). [Author’s Note 2]

John goes on to state, rather confusingly, that “this is he of whom I said, ‘after me comes a man who ranks ahead of me because he was before me’” (1:30). We heard this first in the prologue (1:15). This statement seems to be the gospel’s way of accounting for the similarities between John the Baptist and Jesus while affirming the preeminence of Jesus. This verse describes what theologians call Jesus’ pre-existence. Jesus can only be before John if Jesus, as the Word, exists before John is born.

Finally, John clearly states that he came to baptize “so that [Jesus] might be revealed to Israel” (1:31). Everything in the Gospel of John is centered on Jesus’ revelation. John then testifies to how he knows that this man is Jesus, the pre-existent Word, the Lamb of God: namely, he knows because of what he saw at Jesus’ baptism. The evangelist does not feel the need to show his readers the baptism; John the Baptist’s testimony is enough.

Day Three: John and Jesus (1:35–42)

As we continue to transition between characters, we finally get to encounter Jesus himself — no longer at a distance (1:29), but now “among us” (1:14, 26), or at least among his new disciples. The evangelist pens this story in a typically Johannine way: he gives us the dialogue before introducing us to the main characters. In other words, the interested parties remain “two disciples” (1:37) until they commit to staying with Jesus. Then we learn that they are Andrew and another disciple, soon joined by Simon Peter (1:41–42) on the basis of Andrew’s testimony (1:41). [Author’s Note 3]

Titles become more and more important in this section. When the priests and Levites arrive to question John the Baptist about who he is, his denials of titles like Messiah, Elijah, and “the prophet” become increasingly terse with each question. In theological contrast, the titles granted to Jesus in this chapter are increasingly lengthened and exalted. As we have noted, John the Baptist calls Jesus “the Lamb of God” both in this section and in the previous one (1:29, 36). Yet here Andrew and the other disciple call Jesus “Rabbi,” which, the evangelist explains, means Teacher. Jesus will be a Teacher par excellence in this gospel, explaining not only what Scripture means for the lives of his disciples — one of his roles as a rabbi — but also explaining who he is and who God is. Furthermore, in Andrew’s testimony to his brother Simon Peter, Andrew claims that Jesus is the Messiah, the Anointed One. In other gospels this claim comes much later in the narrative (e.g., Mark 8:27–30). In John, however, titles that describe Jesus are part of the initial testimony to the reader. The evangelist strives to show us immediately who this man, Jesus, is because he knows we’ll need to see his identity in multiple ways [Author’s Note 4].

Day Four: Jesus and Philip’s Testimony (1:43–51)

Throughout John’s gospel Jesus demonstrates remarkable control over, and foreknowledge of, a variety of situations. We see such actions in this passage. On this fourth day, “Jesus decide[s] to go to Galilee,” and “he find[s] Philip and [says] to him, ‘Follow me’” (1:43; cf. 21:22). The narrator gives us a hint that Jesus may have sought Philip because he was from the same city as Andrew and Peter, but there is no additional information in this passage to be certain.

Furthermore, Philip’s immediate response is to find Nathanael and declare, with a new (long!) title for Jesus, that he is the one foretold in the law and the prophets, the one Moses spoke about (1:45; see Deuteronomy 18:18; cf. John 1:21). At the same time, Philip combines this exalted description with Jesus’ parentage: Jesus is the “son of Joseph from Nazareth” (1:45). This paradox gets at the heart of the Gospel of John, and of Christology more generally: how can one from heaven, fulfilling the Scriptures, also be the son of an undistinguished laborer from a small, “no-good” (1:46) village? The rest of the gospel will be spent narrating this paradox, though it does not try to resolve it.

Nathanael objects to this juxtaposition, as will many others in the gospel. However, Philip does not try to argue with Nathanael, but just tells him to “come and see” (1:46). When Jesus demonstrates that he knew Nathanael before they met (1:48), Nathanael is astonished at this display of a prophetic gift. He testifies that Jesus is not just a Rabbi but also the Son of God and the King of Israel (1:49).

This magnificent confession would seem to be the climax of the first chapter of John, but it actually is not. The most significant claim for John’s gospel is still more opaque: Jesus says that Nathanael (and others; the Greek “you” is plural in 1:51) will “see heaven opened and the angels of God ascending and descending upon the Son of Man” (1:51).

It will take the gospel some time to explain all these titles. However, the key statement at the end of Chapter 1 declares that Jesus himself is the ladder to heaven, using imagery from Jacob’s dream at Bethel in Genesis 28:12. This ladder is not something that humans ascend — the angels are doing that. Instead, it might be more precise to say that this Lamb of God, this Rabbi, this Messiah, Son of God, Son of Joseph, King of Israel, and Son of Man is the point at which heaven and earth meet. John will need twenty more chapters and many more descriptive titles to continue telling — and periodically showing — his readers what this claim means.

Questions for Further Reflection

- When the term “testimony” is used in many American churches, it connotes a story about God’s saving power in a person’s life. These testimonies are often told with a focus on the person’s life more than on God’s nature and character. At this point in your life, what would you testify about God? What title(s) for Jesus most accurately reflect(s) his presence in your life now?

- What does Jesus reveal about God in this section of the gospel? Why is this an important introduction to this gospel’s portrayal of Jesus?

- The characters in this section of the gospel embody many of the responses to Jesus that we will see in the rest of John’s narrative. Choose one character (e.g., John, Jerusalem’s priests and Levites, Andrew, Simon Peter, Philip, or Nathanael) and explain how this character’s portrayal in this chapter is similar to or different from your experience with Jesus and his modern-day disciples.

<<Previous Lectio Back to John Next Lectio>>

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons License.