Selections on New Creation Week 10

Socioeconomic Reconciliation: Luke 4:14–21; Isaiah 61:1–4

By David Leong

Associate Professor of Missiology

Read this week’s Scripture: Luke 4:14–21Isaiah 61:1–4

14:57

Enlarge

Enlarge

A few years ago a door-to-door salesman was in my neighborhood selling home security systems. As we chatted briefly on my front porch, he began his pitch. “I don’t mean to sound prejudiced,” he insisted, “but do you realize there’s a lot of Section 8 housing on this block?” His rationale was that the presence of many low-income families nearby should have alerted me to my need for home security. I am indeed concerned about my neighbors, but not out of fear that they will break into my home. Too often we are isolated from our neighbors, and the otherness we fear can easily become an excuse to remain estranged from one another.

Throughout Luke’s gospel, Jesus places love of God and neighbor at the center of the good news he preaches, and this gospel is embodied in a community marked by reconciliation. Jesus’ ministry reenacts God’s grand story of calling and restoring a peculiar people — people who often did not belong together in the eyes of the world. Socioeconomic logic of the day largely functioned to keep the rich and poor apart — what should the privileged have to do with the powerless?

This is why Jesus’ good news in Luke 4:18–19 is so striking: the proclamation of the gospel is the announcement that in God’s economy a new order has begun. In God’s new creation, inaugurated in Jesus, a great reversal of social and economic systems is unfolding. As participants in this new and different ordering of the world, returning to the larger story helps the people of God to inhabit the drama once again, and to imagine the realization of reconciled neighbors in our midst.

Good News to the Poor: Luke 4:14–21

In the opening action of the fourth chapter of Luke, Jesus has triumphed over temptation in the wilderness and is now returning to his hometown “filled with the power of the Spirit” (Luke 4:14). Interestingly, only in Luke’s gospel do we find that Jesus begins his public ministry in Nazareth. While Matthew (Matthew 13:54–58) and Mark (Mark 6:1–6) both include this hometown visit, Luke gives us the most detailed and dramatic account of an encounter that profoundly shapes the character and trajectory of Jesus’ mission.

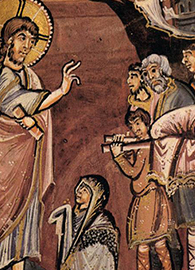

With news and acclaim about Jesus spreading throughout the region, in Nazareth he enters the synagogue on the Sabbath and reads from the scroll of Isaiah with a bold, prophetic proclamation:

The Spirit of the Lord is upon me,

because he has anointed me

to bring good news to the poor.

He has sent me to proclaim release to the captives

and recovery of sight to the blind,

to let the oppressed go free,

to proclaim the year of the Lord’s favor. (Luke 4:18–19)

Few passages in the gospels have said so much by saying so little. In ways that many of his listeners in the synagogue that day would have understood, this is far more than an ordinary Sabbath reading from Israel’s prophets. As he rolls up the scroll and sits down, Jesus offers a stunning statement as he locates himself in the story. “Today,” he explains with every eye “fixed on him” (4:20–21), “This scripture has been fulfilled in your hearing.”

In taking on the mantle of the Lord’s anointing, Jesus inhabits Israel’s sacred texts with both imagination and authority. With intricate and sweeping connections, Jesus is harnessing the prophetic vision of Isaiah 61 and also invoking the weight of Torah in Leviticus 25. Empowered by the Spirit, Jesus’ identification with the Lord’s Anointed One is fulfilling the long awaited hopes of Israel. As a herald of God’s impending reign, Jesus uses messianic language to announce the good news of God’s story breaking into the present. This story is especially good news for the poor, the prisoners, the blind, and the oppressed — all of whom understood the experience of social and economic exclusion in the ancient world. In the new story that God is writing in and through the person of Jesus, a dramatic undoing of those marginalizing forces is now underway.

The final proclamation — “the year of the Lord’s favor” (Luke 4:19) — is the language of jubilee, a sign of holy liberation for all God’s people that was intended to be practiced as a year of Sabbath (Leviticus 25:10). As Jesus looks ahead to the creative forces of renewal that will characterize his gospel ministry, he does so by reaching back into Israel’s tradition and appealing to the Law and the Prophets. But as he is apt to do, Jesus also sees these old texts in a new light, and he is creatively weaving a new thread into the story that connects seamlessly to the original fabric that has been there all along.

Restoration of the Community: Isaiah 61:1–4

As Jesus draws on the opening words of Isaiah 61, it must be kept in mind that the original audience of the prophet’s poetry was intimately acquainted with the broken heartedness of captivity, even after that captivity was technically over. Those returning to Jerusalem from Babylonian exile, as well as those who remained in the traumatic aftermath of foreign occupation, all experienced a kind of “postexilic exile,” [Author’s Note 1] a lingering sense of loss and desolation in the wake of Israel’s defeat and humiliation. Thus Isaiah’s words of comfort are a timely vision of hope: “to proclaim liberty to the captives, and release to prisoners” (Isaiah 61:1) is truly good and healing news for those whose hearts need mending.

The gospel herald in Isaiah goes on to provide “a garland instead of ashes, the oil of gladness instead of mourning, the mantle of praise instead of a faint spirit” (61:3). By embracing the good news of God’s deliverance, the pain and grief of exile are being transformed into a joyful recognition of Yahweh’s saving work. People who are rooted in that hopeful transformation are like “oaks of righteousness, the planting of the Lord, to display his glory” (61:3). The sum result of this transition from mournful captivity to joyful liberation is the restoration of the community:

They shall build up the ancient ruins,

they shall raise up the former devastations;

they shall repair the ruined cities,

the devastations of many generations.(61:4)

The community of exiles was being called to receive the good news of the spirit-anointed servant who saw that Zion could be restored by faithful Israel. However, the act of receiving this gospel was not at all a passive reception of God’s inevitable action to restore his people. Nor was the return to Jerusalem a matter of simple geographic relocation. Quite to the contrary, the invitation to return to Zion was indeed “a return to justice and righteousness” [Author’s Note 2], an active response to God’s initiative that required Israel to keep its covenantal commitments to Yahweh. Only in maintaining justice and righteousness would Israel see its community restored through receiving the good news of God’s saving presence in their midst.

Jubilee Justice and Righteousness: Leviticus 25

“The year of the Lord’s favor” that Jesus proclaims at the end of his reading of Isaiah (Luke 4:19) is an embodiment of this communal justice and righteousness in the life of Israel. In a sense, jubilee functions like a massive societal reset button that occurs once every fifty years. [Author’s Note 3] However, framed within in the broader Levitical context of Israel’s collective holiness, the year of jubilee was not merely a social and economic restructuring of society. First and foremost, this was a spiritual commitment that grew out of a loving covenant with Yahweh. Celebrated as a Sabbath of Sabbaths, jubilee begins on the Day of Atonement (Leviticus 25:9), which is a communal marker for repentance of the sins of the people that result in the exploitation of the poor and vulnerable. In this way, the social and economic ordinances that define the practices of jubilee are rooted in a spiritual conviction that the redistribution of land, labor, and resources is an act of obedience to the holiness code that reconciles the community to God.

While “jubilee was intended to prevent the accumulation of the wealth of the nation in the hands of a very few” [Author’s Note 4], other economic policies of the year of the Lord’s favor worked to equalize social opportunity through corrective measures of rest and return. The liberation of slaves and the compassionate treatment of the poor provided concrete outcomes for those on the bottom of the social ladder. Ultimately, jubilee reminds the people of God that they are stewards — and not owners — of the land, labor, and resources that they have been entrusted. These assets of the material economy were gifts to be managed for their flourishing, not commodities to be exploited. Treating workers fairly, lending without interest, welcoming foreigners, and freely redistributing wealth are each reflections of an alternative economy in which Yahweh is the ultimate judge of justice and righteousness.

From Text to Life: Forming a New Community

In returning to the synagogue in Nazareth, we can listen afresh to Jesus’ gospel announcement with all the depth and richness of the Law and the Prophets woven into his reading. Below the surface of Luke 4:18–19 is the hope and longing of exiles returning home, set within the old story of Israel’s alternative community and its witness of social and economic holiness. Surrounding it all is a promise of good news for the poor and oppressed when the people of God embrace justice and righteousness for the healing of their land, community, and society.

How can the church — as heirs of the same story and participants in its ongoing drama — begin to listen more closely for the cues and cadence of reconciliation in God’s new creation? How can we move more intentionally toward a transformative encounter with the person of Jesus who taught with authority that day in Nazareth as he began his public ministry? I want to suggest a few simple ways to avail ourselves to the truth of the gospel that turns us toward our neighbors in love and compassion.

First, we cannot underestimate the resistance we will face in the pursuit of socioeconomic reconciliation. The structural barriers that serve to keep us apart, and the rationalizations for accepting estrangement as “normal” are very real. Fear, prejudice, and ethnocentrism play as much a part in Luke 4 as they do today. Sadly, as we read on in the text, the reaction of those in the synagogue at Nazareth was less than hospitable to say the least. The good news Jesus preached was not only for the poor and oppressed, but also for Israel’s “pagan” Gentile neighbors. The thought that unclean and immoral “others” could be included in God’s grand story to restore creation was simply too far afield for many good religious Jews to accept. The uniqueness of election — of being chosen for God’s purposes — tends to have a way of obscuring the possibility of social and economic others being included in those plans. And yet a close reading of the biblical story reveals that “the faith of the outsider” [Author’s Note 5] has always been an essential ingredient in God’s redemptive purposes in the world.

When the people of God take seriously the call to embrace those on the socioeconomic margins of our own hometowns, we must anticipate that the reaction of the religious establishment may be to throw us off a cliff — hopefully a metaphorical one! I offer this insight not as a pessimist about the church’s capacity to embrace others, but rather as a realist about how deep the patterns of exclusion run through each of us as individuals and through the systems we create in society. It is an important warning for us to heed, as Dr. Willie Jennings cautions us: “it is not at all clear that most Christians are ready to imagine reconciliation.” [Author’s Note 6] Though Jesus’ prophetic announcement in Nazareth was initially met with hostility, those with ears to hear and hearts to understand carried the message onward with the genuine belief that it truly was good news.

Secondly, in pursuit of walking the same path that Jesus’ disciples took into harm’s way, we must see the work of socioeconomic reconciliation as both structural and relational. Jubilee was a corrective measure at the policy level of Israel’s social codes, but it was also reflective of a covenantal relationship with Yahweh, who sought to cultivate holiness in his people. In the same way, the people of God today must advocate for policies and structures that reflect God’s justice and righteousness. Given the complexities of our socioeconomic systems, this is never an easy or straightforward task. But the church cannot shy away from the responsibility to engage these systems in solidarity with the poor and for their benefit.

Ultimately, this advocacy is entrusted not to individual activists or political campaigns, but to a particular community. Socioeconomic reconciliation has been deeply embedded in the DNA of the people of God from the very beginning, and we catch glimpses of this reality when the story of God’s reign is made manifest among us. Stanley Hauerwas suggests that,

The most creative social strategy we have to offer is the church. Here we show the world a manner of life the world can never achieve through social coercion or governmental action. We serve the world by showing it something that it is not, namely, a place where God is forming a family out of strangers. […] The gospel begins […] with the pledge that, if we offer ourselves to a truthful story and the community formed by listening to and enacting that story in the church, we will be transformed into people more significant than we could ever have been on our own. As Barth says, “[The Church] exists […] to set up in the world a new sign which is radically dissimilar to [the world’s] own manner and which contradicts it in a way which is full of promise” (Church Dogmatics, 4.3.2.). [Author’s Note 7]

I didn’t buy a home security system from the salesman that day, but I wish we could have spoken a bit longer. I would have shared with him how God is forming a family out of strangers, however imperfectly, in our little congregation down the street. It’s a community where socioeconomic differences are pronounced, but our commitment to being neighborly runs deeper than our fears. We don’t always get it right, but we’re trying to live into the story that Jesus tells: we belong to each other, and that’s good news.

<<Previous Lectio Back to Selections on New Creation Next Lectio>>

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons License.