Selections From Israel's Story Week 6

Strange Fire: Leviticus 10

By Sara Koenig

Seattle Pacific University Associate Professor of Biblical Studies

Read this week’s Scripture: Leviticus 10

10:13

Enlarge

Enlarge

The name “Leviticus” is the title of this book in the Septuagint, meaning in Greek, “of the Levites.” The Levites, of course, are the tribe that makes up the priests, so that name points to the nature of this biblical book as a book for the priests and priestly matters. Its early rabbinic name is Torat Kohanim, the priests’ manual [see Author’s Note 1].

The Message of Leviticus

In many ways, Leviticus is a simple book. Its main message is that God is holy, and humans are not, and most of the book is about ways to overcome that gap. Leviticus is also in many ways a comforting text because there is no guess work about what to do; Leviticus gives very specific instructions about offerings and sacrifices, prescribing what should be done in every circumstance when an offense is committed. The law is clear, and the directions are exact.

But in other ways Leviticus is very complicated and foreign, with bewildering technicalities about offerings and arcane details about making sacrifices. Perhaps that means that we have to work a bit harder to see its relevance, but it is an effort that is worthwhile. As the third book in the Pentateuch, it is the center of the Torah, and its content is central for understanding the relationship between God and humans.

Nadab and Abihu

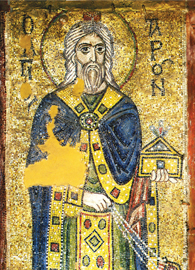

The text for this week is challenging not only because of all the details it includes about offerings, but because of the horrific event that happens at the very beginning of the chapter. We first met Aaron’s sons Nadab and Abihu in Exodus 24, when they were invited by name to go up the mountain to worship the LORD in Exodus 24:1; Exodus 24:9-10 tells us that there they saw the LORD.

In the chapter immediately preceding ours, we find out that this is the first day that Aaron and his sons are ordained and can begin their official priestly ministry. It turns out to be the last day for the sons. The tragedy is told incredibly briefly:

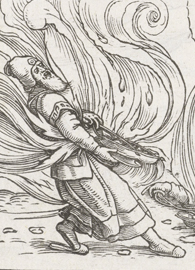

Now Aaron’s sons, Nadab and Abihu, each took his censer, put fire in it, and laid incense on it; and they offered unholy fire before the LORD, such as he had not commanded them. And fire came out from the presence of the LORD and consumed them, and they died before the LORD (Leviticus 10:1–2).

Such an event has very little explanation given. One clue is the adjective describing the fire: unholy. Some translate this word as “unauthorized,” but the word historically means “strange,” or “foreign.”

The clause that follows gives some more detail — it was not what God had commanded. There is a measure-for-measure principle present here: Aaron’s sons transgress by fire, and are subsequently punished by fire. The fire that kills them comes liphney adonai, which is translated two ways in Leviticus 10:1–2, as “the presence of the LORD” and “before the LORD.” It is, however, the same phrase in Hebrew: they offered strange fire in the presence of the LORD, and fire came out from the presence of the LORD, and they died in the presence of the LORD.

Moses then gives an explanation to Aaron. Different rabbis puzzled over the location of God’s saying: one suggested Exodus 29:43, while others pointed to Exodus 19:22, and Leviticus 8:33–35 — though none of these exactly matches the citation.

Aaron’s Response to the Death of His Sons

In response, Aaron was silent. We might wonder if Aaron is silenced by Moses, or if he simply has nothing to say. The latter would be quite appropriate — what could be said in response to the sudden, tragic death of your sons followed by the definitive (if callous) reason given by your brother?

Moses then takes over in 10:4–7, commanding the removal of the bodies and commanding the remaining family members not to mourn. Moses does, however, allow that “your kindred, the whole house of Israel, may mourn the burning that the LORD has sent” (10:6). Then Moses commands them not to go outside the entrance of the tent of meeting or else they will die, because the anointing oil of the LORD is on them. Aaron and his two remaining sons, Eleazar and Ithamar, do as Moses ordered.

On one hand, their obedience may not be surprising — they have just witnessed the death of their sons and brothers, and know that the warning that they may die if they disobey is not an idle threat. On the other hand, they are commanded to stay in the very place where Nadab and Abihu were killed! Their obedience, then, reflects their own faith and trust.

Enlarge

Enlarge

More Instructions

Leviticus 10:8–11 contains more instructions from God, which at first glance may seem like a non sequitur, but upon closer look are intimately connected with the themes in this chapter. God makes clear that drinking alcohol before entering the tent of meeting is to be avoided, lest they die (10:9) — something that had not previously been commanded.

The instruction that they are to distinguish between holy and common, unclean and clean (10:10) is one of the essential functions of priests, and it presumes that priests are themselves aware of that distinction. Finally, we read about the priests’ role and importance in communicating God’s requirements to the people: the LORD speaks statutes through Moses that they are to teach to the people (10:11).

There is a hierarchy given — Moses remains as God’s mouthpiece, but the priests are responsible for instructing the people about God’s commandments. Indeed, this section highlights why and how it is important that the priests follow exactly what God commands them to do, something that Nadab and Abihu did not do.

In Verses 12–15, Moses gives some more instructions to Aaron, Eleazar, and Ithamar, about eating the offerings. Though these may also seem minor in importance compared to what happened at the beginning of the chapter, the way Verse 12 refers to Eleazar and Ithamar as “his remaining sons” won’t let us forget what happened to Nadab and Abihu. Their death continues to cast its shadow throughout this chapter.

Moses’ Anger Over the Sin Offering

Then we read in 10:16 that, after Moses asks about the goat of the sin offering and finds out that it has been burned, Moses gets angry [see Author’s Note 2]. Some context helps explain Moses’ response: in Leviticus 6:26 and 29, God commanded that the sin offering was to be eaten by the priests. In Israel’s contemporary world, there was a belief that an animal sacrificed for sin would itself be full of sin and impurities, and should not be eaten.

Therefore, the explanation that it is holy, and the practice of eating that meat, would set Israel apart from the surrounding nations and religions. Aaron, however, gave an explanation as an excuse for why the meat had been burned, and not eaten — that this particular sacrificial meat had been doubly polluted by sin and the death of his sons; therefore they followed the more stringent procedure of destroying rather than eating it (compare Leviticus 6:30).

The chapter ends by telling us that Moses agreed with Aaron’s explanation, signaling once again that, even though the priests play a vital role in Israel’s worship, Moses remains the authority.

There is no further conversation about Nadab’s and Abihu’s deaths, or the great loss they must have been to Aaron. Ultimately, this chapter is about duty, about continuing to do what God tells you to do even amidst personal tragedies. It tells, with a stark example, the importance of obeying even the tiny details of God’s commands.

Questions for Reflection

- The Lectio writer acknowledges that Leviticus has often been a difficult book for the contemporary church to read. Has this been true for you? Why or why not? What posture should we take toward Leviticus and other texts that seem culturally removed from our setting?

- In your own words, define “holy” and “unholy.” Why does the book of Leviticus spend so much time on the topic of holiness? In what way is holiness important—or unimportant—to your faith? Has reading this text challenged your answer to this question?

- What is your reaction to the story of Nadab and Abihu? Why do you think that the tragedy of their deaths is told with so little commentary or detail?

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons License.