Selections From the Prophets Week 14

The Faithful Remnant: Malachi 3:6–18

Professor of Christian Ministry, Theology, and Culture

Read this week’s Scripture: Malachi 3:6–18

11:54

Enlarge“Something Noble, Which Cannot Be Destined for the Worms”

Enlarge“Something Noble, Which Cannot Be Destined for the Worms”

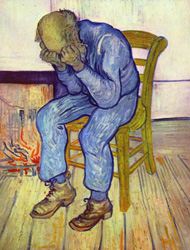

In one of his paintings, “At Eternity’s Gate,” Vincent Van Gogh portrays an old man sitting by a fireplace with his head buried in his hands. In a letter to his brother Theo, Vincent describes what motivates and animates his portrait:

In my painting “At Eternity’s Gate,” I have tried to express what seems to me one of the strongest proofs of the existence of God and eternity — certainly in the infinitely touching expression of such a little old man, which he himself is perhaps unconscious of, when he is sitting quietly in his corner by the fire. At the same time there is something precious, something noble, which cannot be destined for the worms … This is far from theology, simply the fact that the poor little woodcutter or peasant on the heath or miner can have moments of emotion and inspiration which give him a feeling of an eternal home, and of being close to it. [Author’s Note 1]

This is the tension of the “now and the not yet,” as many people struggle under the weight of the life they live. Perhaps you feel it — this sense that all the pain, suffering, longing, despair, and anguish that we see every day on the news around the world, in our neighborhoods, in the eyes of coworkers, and in the heavy sighs of family members, is evidence that we were meant for another life free from all this.

For some there is a wish for ignorance, for not feeling that there has to be more to this life than merely living or dying. Others choose to inoculate themselves through entertainment or other means to stave off this longing for something more. Yet the prophets have not given us the option to ignore or sublimate this nagging sense that something more is just beyond the horizon, and we have a role to play in lifting the clouds of darkness not only for ourselves but for others we are called to.

To live as the prophets lived was to live theologically near-sighted and far-sighted at the same time — to have a clear and present understanding of the pain, sorrow, joy, and confusion of this life as well as to live and proclaim the reality of the promises of God. To know that there is indeed more to this life than what we see around us is to live as the prophets lived. Many can identify with the old man described by Van Gogh in “At Eternity’s Gate” — the notion that when no one is watching, we bury our head in our hands overcome with “emotion and inspiration.” It is with this image in mind that we turn now to our final prophet in the Old Testament.

Malachi — “My Messenger”

The name Malachi in Hebrew means “my messenger,” and some commentators hold that the name was given to the book as a placeholder for an anonymous prophet who is referred to in 3:1:

See, I am sending my messenger to prepare the way before me, and the Lord whom you seek will suddenly come to his temple.

The dating of the prophecy places the book in the Second Temple period. In 1:6–14 the prophecy mentions corruption of the priesthood that would have been addressed during the time of Ezra and Nehemiah, placing Malachi prior to 458 B.C. [Author’s Note 2] One of the key things we find in Malachi is that justice and mercy find equal space in the discourse. While God seeks to eradicate all that stands in the way of his kingdom, we also hear that God desires to save those who are pure of heart and preserve them as a remnant so that the nations and generations to come will see the Lord’s mercy and grace.

This tension between justice and mercy is a challenging topic in Rabbinic Judaism, and something that the prophets struggle with as well. How can justice and mercy co-exist? For Abraham Heschel, these two attributes both point to God and yet acknowledge that God transcends both justice and mercy: “Justice is a standard, mercy an attitude; justice is detachment, mercy attachment; justice objective, mercy personal. God transcends both justice and mercy.” [Author’s Note 3]

That God stands above both justice and mercy helps us to see and hear what the prophets have been challenging us with thus far: God is truly free to bless and to curse, yet the nature of God is beyond our simple categories of morality. That God is more than justice and more than mercy speaks volumes to trusting in the ways of God beyond our own codes, rules, and laws. Akin to our reflections on Zechariah in Lectio 11, where we saw the danger of choosing “walls” over faithfulness, Malachi also shows us that the movement of God in the world is beyond our ability to reason or even imagine. Like the man in Van Gogh’s painting, it is tempting to bury our head in our hands — but that doesn’t mean that God isn’t working.

“You Have Said … but I Say …”

One of the distinctive aspects of Malachi is the method by which the prophet employs literary rhetorical methods such as parallelism and chiasmus [Author’s Note 4]. He makes his case not merely with appeals to history, but with language that bridges points and makes connections in tone as well as text. Throughout the four chapters, the prophet puts forth a series of charges that have been leveled against God in a mode that is as poetically provocative as it is historically arresting:

- “I have loved you, says the LORD. But you say, ‘How have you loved us?’” (1:2)

- “‘[I]f I am a master, where is the respect due me?’ says the LORD of hosts to you, O priests, who despise my name. You say, ‘How have we despised your name?’” (1:6)

- “Have we not all one father? Has not one God created us? Why then are we faithless to one another, profaning the covenant of our ancestors?” (2:10)

- “You have wearied the LORD with your words. Yet you say, ‘How have we wearied him?’ By saying, ‘All who do evil are good in the sight of the LORD, and he delights in them.’ Or by asking, ‘Where is the God of justice?’” (2:17)

- “’Ever since the days of your ancestors, you have turned aside from my statutes and have not kept them. Return to me, and I will return to you,’ says the LORD of hosts. But you say, ‘How shall we return?’” (3:7)

- “’You have spoken harsh words against me,’ says the LORD. “Yet you say, ‘How have we spoken against you?’” (3:13)

This rhetorical method is similar to that which is employed by Jesus in the Sermon on the Mount in Matthew’s gospel, such as in Matthew 5:21–22:

You have heard that it was said to those of ancient times, “You shall not murder”; and “whoever murders shall be liable to judgment.” But I say to you that if you are angry with a brother or sister, you will be liable to judgment; and if you insult a brother or sister, you will be liable to the council; and if you say, “You fool,” you will be liable to the hell of fire.

This device rolls out a scroll of judgment before the priests, the royalty, and all those who seek to oppress God’s people with sly justifications and legalism — and ultimately allows the Law itself to indict them. Throughout these “Yet you say” indictments of rhetoric, God’s reply builds to a culminating point found in Malachi 3:16–18:

Then those who revered the LORD spoke with one another. The LORD took note and listened, and a book of remembrance was written before him of those who revered the LORD and thought on his name. They shall be mine, says the LORD of hosts, my special possession on the day when I act, and I will spare them as parents spare their children who serve them. Then once more you shall see the difference between the righteous and the wicked, between one who serves God and one who does not serve him.

What we have here echoes the response of God that we have heard throughout the Lectios addressed in our selections from the prophets, yet perhaps with a more resolute statement and affirmation. Over and over, the prophets have been calling the people of God to acknowledge the call to justice (mišpāṭ), to righteousness (ṣedāqâ), and to a continued plea to turn (hāpak) away from sin and fully face the God who formed them, nurtured them, and has sustained them through exile and oppression, and who will continue to do so for generations to come. They will not be forgotten. On the contrary, their names will be remembered in a “book of remembrance” (3:16) and be numbered with the likes of Moses and Elijah (4:4).

This high esteem placed on the faithful, lowly, righteous, and just is to comfort them and silence for them any concern that the momentary struggles they face presently will be their enduring lot. Rather, their life will be preserved as a remnant, and, for those who revere the name of God, “the sun of righteousness shall rise, with healing in its wings.” (4:2)

In the first Lectio of this series, we spoke of 1 Kings 18:20–40, where Ahab gathers all the Israelites on Mount Carmel for a showdown between the prophet Elijah and the prophets of Baal. In Verse 21, the prophet Elijah sums up the scenario: “Elijah then came near to all the people and said, ‘How long will you go limping with two different opinions?’” Here in Malachi things come full circle as the promise is given that Elijah will return:

Lo, I will send you the prophet Elijah before the great and terrible day of the LORD comes. He will turn the hearts of parents to their children and the hearts of children to their parents, so that I will not come and strike the land with a curse. (4:5–6)

In a similar fashion to our discussion of 1 Kings 18:20–40, this too will not be a season for limping, but a season for “leaping like calves from the stall.” (Malachi 4:2) In this way, Malachi — the “messenger” — sounds the last note as the Old Testament closes and the voices of the prophets fall silent for the next 400 years prior to the coming of John the Baptist and the birth of Christ.

With this prophet we are left with God’s answering the generations not with total destruction, but with a judgment that preserves a remnant of hope. This prophecy underscores the familiar prophetic narrative: God is eternally faithful from generation to generation. In the end of our Old Testament the promise is given that God will preserve those who are faithful, that the generations of righteousness will thrive, and that no curse will ever be the last word.

This is the promise of God through the generations of prophets that we have reflected on over these 14 weeks, and this God, as we hear in Malachi 3:6, does not change — “therefore you, O children of Jacob, have not perished.”

These are the words of the prophet Malachi for the people whom Vincent Van Gogh desired to paint with dignity and nobility. These are the words to those who bury their heads in their hands, working so very hard to make ends meet, to live honorably, faithfully, humbly, and with hope, faith, and love in their body, mind, and soul. Perhaps this is the word for you. Perhaps this is the word for someone you know who is discouraged and seeking some solace in the storms of this life.

“See, the day is coming, burning like an oven” (4:1), says the Lord.

Yes indeed … the day of the Lord is coming.

And it will be a wonder to behold.

Questions for Further Reflection

- Malachi utilizes a form of rhetoric where he begins with complaints to God and then allows God the space to respond. What complaint(s) would you bring to God, and how do imagine God would respond to these complaints?

- Malachi ends with a reminder we have seen in other prophets — the promise of a remnant of faithful followers who will always be preserved even in the darkest of times. What are examples of remnants in the world today — people or communities that seem to show the promise of God’s faithfulness even in the midst of oppression?

- Those whom God will save are to have their names written in a “book of remembrance.” When you think of God writing your name in such a book, in what ways does this encourage you in your faith? What do you imagine God writing next to your name to describe what he sees in you that is to be “remembered”?

<<Previous Lectio Back to Selections From the Prophets Next Lectio>>

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons License.