1 & 2 Samuel Week 1

The Preview: 1 Samuel 1:1–2:10

Seattle Pacific University Associate Professor of Biblical Studies

Read this week’s Scripture: 1 Samuel 1:1–2:10

16:22

I am a big fan of movie previews, and there seems to be a particular formula to the good ones: They tell you enough about the film as a whole so you know whether you want to see it, without giving away the entire plot. The first two chapters of 1 Samuel — Hannah’s story and song — function like a good preview of 1 Samuel and 2 Samuel [see Author’s Note 1]. Three of the major themes that will run throughout the books appear in these beginning chapters. Thus, we know generally what these books are about, but we must read on to find out exactly what will happen and how.

First, Hannah’s story and song introduce us to the theme of God’s provision meeting human hurts and hopes. Hannah’s barrenness causes her deep bitterness and grief, but God opens her womb and gives her a child. We read over and over again in 1 & 2 Samuel about a God who responds to human frailty and need. The second theme requires a spoiler alert: Even before the nation of Israel asks for a king in 1 Samuel 8, Hannah’s song talks about how God will “give strength to his king, and exalt the power of his anointed” (1 Samuel 2:10). In fact, the huge and perennial questions — “Who is God?” and “Who are God’s people?” — get asked within the lens of these books and examined in the narrower focus on monarchy in Israel. Third, Hannah’s song celebrates the theme of God reversing status and fortune: making the full hungry and the hungry full, raising up and bringing low. Obviously Hannah’s status as a barren woman is reversed, as 1 Samuel 2:5 says, but reversal also happens for others. Saul, raised high to become Israel’s first king, will be brought low. And David, the youngest and forgotten son (1 Samuel 16:11), will rise to be Israel’s greatest king. At the height of his rule, David will also fall because of his own sinfulness; but there, too, God will be merciful.

Of course, Israel did not always have a king, as the book of Judges reminds us [see Author’s Note 2]. The final verse of Judges states, “In those days there was no king in Israel; all the people did what was right in their own eyes” (21:25). The fact that Israel has no king gets repeated another three times, in Judges 17:6, 18:1, 19:1, almost as a refrain for the final chapters of Judges. Those chapters tell of horrific violence against a single woman, which leads into a civil war and the breakdown of the social fabric of Israel, including more violence against women. Nijay Gupta, in his Lectio on Joshua and Judges, titles this section “Israel with Two Black Eyes.” This is no glossy, whitewashed history. Gupta explains, “The reminder that at this time there was no king was the narrator’s way of pointing ahead to a time where good King David would bring cohesion — what military forces call ‘esprit de corps’ — to the people of God.” When the books of 1 & 2 Samuel begin, there is no king; the political setting is that of a loose federation of tribal groups. But when the books of 1 & 2 Samuel end, there is a centralized government.

Still, monarchy (and the way it is presented in the text) is complex. On the one hand, kingship is good. A good king will ensure that there is order and social cohesion. Beyond being a relative improvement compared with the time of the Judges, a good king can rule on earth as God does in heaven, caring for the poor and needy in the land (Psalm 72:12–14). On other hand, when Israel asks for a king, they are rejecting the LORD as their king (1 Samuel 8:7), and there is no guarantee that all the kings will be good ones. Eventually the corruption in the monarchy (detailed in 1 & 2 Kings) is what leads to Israel’s exile.

Even the good King David abuses his power — most notably in his adultery with Bathsheba and the murder of her husband, Uriah, but also in his failure to respond to his daughter, Tamar’s, rape, and in the census David takes in 2 Samuel 24. The consequence of the census is a plague against the people of Israel. The plague ends only after David prays for God to have mercy (2 Samuel 24:15–25). That final chapter of 2 Samuel parallels the beginning of 1 Samuel: Human failure and frailty are met with God’s gracious answers to prayers.

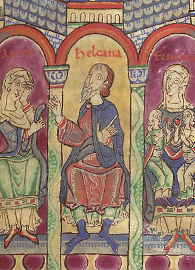

EnlargeHannah and Elkanah

EnlargeHannah and Elkanah

1 Samuel 1 starts with a lengthy introduction to Elkanah. With all the details given about his lineage, we might miss the significant detail in 1:2 that Hannah, Elkanah’s wife, is barren. Hannah is certainly not the only barren woman in the Bible; the Old Testament narrative has already introduced Sarah, Rebekah, and Rachel as biblical characters who share this trait. Indeed, the biblical world is one in which a woman’s worth and role are chiefly measured by her ability to bear children. Even today, when women enjoy more opportunities, infertility can be a hard and painful thing.

Hannah, whose name means “favored” or “gracious,” is only one of Elkanah’s two wives. The other wife, Peninnah, has children — which is not surprising given that her name means “fertile” or “prolific.” But this fertile wife is also cruel to Hannah. Described as a “rival” to Hannah, Peninnah provokes Hannah over her childlessness. Elkanah, we are told, loves Hannah regardless of her inability to have children, and gives her twice as much to eat as he does Peninnah and her children [see Author’s Note 3]. Hannah does not eat, however, but only weeps. Elkanah asks her four questions: “Why do you weep? Why do you not eat? Why is your heart sad? Am I not more to you than ten sons?” (1:8). But Hannah does not answer him. Instead she prays to the LORD. All of these events take place in Shiloh, where the ark of the covenant is located. The ark is the container for the tablets of the Ten Commandments, and it represents God’s presence. It will play an important role later in the books of 1–2 Samuel.

We’ve been told about Hannah’s weeping, and now 1 Samuel 1:10 tells us that she is embittered. As Hannah prays she makes a vow that if she has a child, she will give the child to God. Included in her vow are other details that tell us that the child will be a nazirite (1:11) [see Author’s Note 4]. This means, among other things, that he will abstain from alcohol. Ironically, as Hannah is making this vow, the priest Eli thinks she is drunk and commands her to put away her wine (1 Samuel 1:14). Eli will misinterpret a number of things in the future. This introduces him to us as fallible, but also as a man of God.

Hannah answers Eli and tells him her situation. She is not drunk, but instead is “deeply troubled” (1:15) and does not want to be counted as “worthless” (1:16). Both of those phrases deserve comment. The “deeply troubled” is more literally “hard in spirit,” and though the phrase only occurs here, it might recall a hardness of heart as in Exodus 7:3. “Worthless” (Hebrew blyʿl) is a word used later to describe Eli’s sons. These characteristics, however, will not ultimately define Hannah.

Eli’s response is twofold: He tells Hannah to go in peace, and then he says, “the God of Israel grant the petition you have made to him” (1 Samuel 1:17). To this Hannah responds, “Let your servant find favor in your sight” (1:18). The word translated as “favor” is related to Hannah’s own name, and we are not likely to be surprised when the favored woman will indeed find favor not only with Eli, but with God. Additionally, Hannah’s “favor” has resonance with Mary, the mother of Jesus, who is greeted by the angel Gabriel with the title “favored one” (Luke 1:28).

Hannah’s petition to God is granted: she conceives, gives birth to a son, and calls him Samuel, which means “I have asked him of the LORD,” according to the text (1 Samuel 1:20) [see Author’s Note 5]. When Hannah asked God for Samuel, she also vowed to give him to God, and she makes good on her vow after Samuel is weaned. We don’t know exactly how old Samuel is at this point; 1 Samuel 1:24 says in Hebrew, “the lad was but a lad,” possibly around 5 years old. Both of Samuel’s parents bring him to Shiloh, where they make offerings to God and give Samuel to Eli. Hannah reminds the priest that she was the one who prayed to God for the child, and since God answered her petition she is therefore presenting Samuel to God. The Hebrew word in 1:28 gets translated in different ways: in the NIV Hannah “gives” Samuel to God; in the RSV, ESV, and NRSV she “lends” him to God; and in the NASB she “dedicates” him to God [see Author’s Note 6]. Hannah will return, as 2:18–21 tells us. She sees her son every year and makes him a robe of the sort worn by priests.

EnlargeHannah’s Song

EnlargeHannah’s Song

Hannah responds to all these events in a poem that has been identified both as a prayer and as a song, which might make us consider how prayers can be sung and songs can be prayed. This poem begins and ends with the affirmation that human strength comes from and is exalted in God. God is incomparable; there is no other like this God, who knows and also weighs actions (2:2–3). The heart of this poem (2:4–8) affirms that God is one who makes surprising reversals, making the strong weak and the weak strong. In fact, God does both negative and positive things: On the negative side, God “kills,” “brings down to Sheol,” “makes poor,” and “brings low.” The positive list, however, is longer: God “brings to life,” “raises up,” “makes rich,” “exalts,” “raises up the poor from the dust,” and “lifts the needy from the ash heap” to “sit with princes and inherit a seat of honor” [see Author’s Note 7].

The royal language does point toward kingship in Israel, but there is a broader application: that God generally is one who makes first those who are last, and who honors those who are humbled. 1 Samuel 2:9 concludes with the statement “not by might does one prevail.” Indeed, all the human ways to exert power fall short in comparison with God, who can reverse human circumstances of status and power entirely. With this in mind, the explicit reference to a king in 2:10 falls into proper perspective, as the king — the anointed one — only has strength given by God.

Hannah’s poem has connections with three other texts. First, it is linked with 2 Samuel 22, a victory song of David that also celebrates God’s power and strength to save those who trust in God. David’s song appears toward the end of the books of Samuel as a nice complement to Hannah’s song at the beginning, since the contents of both are related. A second text with close connections to Hannah’s poem is Psalm 113, a hymn of praise that also describes how God “raises the poor [and] needy […] to make them sit with princes” and gives children to “the barren woman” (Psalm 113:7–9). Third, Hannah’s song is very similar to Mary’s song in Luke 1:46–55. Mary is visited by the angel Gabriel and told that she will be the one to bear the Messiah, whom she will name Jesus. She responds by praising the God who brings down and lifts up, who sends the rich away empty and fills those who are hungry —the same theme of reversal we see in Hannah’s prayer. This passage in Luke containing the annunciation of the ultimate King echoes the passage that foretells Israel receiving its first king.

The final verse in this section (1 Samuel 2:11) tells us that though Samuel’s parents return home, Samuel will stay with Eli. Strangely it is only Samuel’s father, Elkanah, who is named here; though Hannah has been the focus of the first two chapters, she is not named. This could be because her presence is just assumed when her husband is mentioned, and it is likely not any comment on her “worth.” Rather, by naming just the two men — Samuel’s biological father and Eli the priest, under whom Samuel will minister before God — the text is giving us a preview of the familial ties that will be discussed in next week’s Lectio.

Questions for Further Discussion

- For Israel, kings are a mixed blessing. As mentioned, there are positive and negative consequences when Israel asks for a king. Can you think of other ways in which kings could be a good thing? How about other ways in which kings could be a bad thing?

- Reread Hannah’s song/prayer (1 Samuel 2:1-10). What in this text resonates with you? What in this text challenges you? Can you think of other places in Scripture where God makes “surprising reversals”? Where do you see God making surprising reversals in your own life, or in your local community?

- The birth of Samuel has similarities to the birth of Jesus, and some connections between Hannah and Mary are noted above. What other connections do you see between today’s Lectio reading and the birth and life of Jesus?

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons License.