Luke Week 9

“To Jerusalem and Opposition”: Luke 18:31–21:37

By Mark Abbott

Seattle Pacific University Adjunct Instructor

Read this week’s Scripture: Luke 18:31–21:37

17:14

Enlarge

Enlarge

In a compelling mystery novel, tension builds. Conflict between characters intensifies. A sense of foreboding increases. There may be a dark foreshadowing of what is to come, and we brace for the climax toward which we are being drawn. It’s often the same with a great piece of music. The composer builds tension between musical themes to be resolved in a great climax toward the end of the piece.

In this Lectio segment, tension builds toward a climactic resolution. But that resolution will come only with the crucifixion and resurrection of Jesus. Beginning in Chapter 9, we heard Jesus tell his followers, “The Son of Man must undergo great suffering and be rejected by the elders, chief priests, and scribes, and be killed, and on the third day be raised” (9:21). Again he says, “The Son of man is going to be betrayed into human hands” (9:44). But this is all beyond the disciples’ comprehension. Luke writes, “Its meaning was concealed from them, so that they could not perceive it” (9:45).

Luke 18:31–34: Once More … Trouble Ahead!

With Luke 18:31, the darkness and foreboding we have been sensing in the story increases. The second half of the verse is unique to Luke. “Everything that is written about the Son of Man by the prophets will be accomplished.” Luke’s artistry looks backward to Old Testament prophesy. But the gospel writer also looks ahead beyond the gathering clouds and anticipates light being shed after the resurrection on the blinded minds of Jesus’ followers.

For instance, in the Emmaus Road story (Luke 24:13–32), Jesus, incognito, opens the eyes of two disciples — on their sad journey home on the first Easter Day — to all that the Old Testament says about him. Luke tells us, “Beginning with Moses and all the prophets, he interpreted to them the things about himself in all the scriptures” (24:27). Again to the gathered followers in Jerusalem, Jesus says, “everything written about me in the law of Moses, the prophets, and the psalms must be fulfilled” (24:44).

Tension in the story will be resolved when the link between Jesus and the Old Testament is clearly understood by post-resurrection believers.

But that will be in the days ahead. Right now, the journey that had begun back in Luke 9:51 is developing in darkness and tension as Jesus and his followers go the final miles up to Jerusalem. Despite one more warning to Jesus’ followers, “they understood nothing about all these things; in fact what he said was hidden from them” (18:34).

Luke 18:35–19:10: Responding in Faith

Jerusalem is 17 miles uphill from Jericho. Before starting that long, uphill road in the environs of Jericho, Luke places two stories of faith response to Jesus. While the disciples don’t get it, a blind beggar and a socially outcast tax collector do. They both respond in faith to Jesus.

The blind man, Bartimaeus in Mark’s account (Mark 10:46), hearing that Jesus is passing by, cries out, “Jesus, Son of David, have mercy on me!” (Luke 18:38). He persists in his outcry despite the well-meaning protectiveness of those around Jesus. While they see a blind beggar as a social outcast, Jesus sees him as a person in need.

“What do you want me to do for you?” Jesus asks. The most likely response by a roadside beggar in Jesus’ day would be to ask for alms. After all, blindness is his way of securing a living from the alms of passersby. But this seeker after Jesus refuses to scale back his request, asking instead for the ultimate: “Lord, let me see again” (18:41). Jesus declares, “Receive your sight!” and, commenting on the blind man’s persistent and intense plea for mercy, adds, “your faith has saved you” (18:42).

As we have seen, faith for Luke is not an intellectual assent to truth as much as a persistent, heartfelt, laying of ourselves and our needs before Jesus.

Zacchaeus, celebrated in a popular children’s song, encounters Jesus as he passes through Jericho. A border city where customs and toll were collected, Jericho was also a wealthy city. Presumably there was extensive tax income for Zacchaeus, who was a “chief tax-collector” and a wealthy man. Zacchaeus was also short in stature — in the context of that day, probably less than five feet tall. So intensely did he want to see this Jesus, about whom he had surely heard much, that Zacchaeus engages in the undignified action of climbing a tree. Imagine a rich businessman in ancient robes scaling a tree!

From its branches, Zacchaeus can see Jesus and be seen by him. Again, Jesus chooses to spend time with social and religious outcasts, inviting himself to Zacchaeus’ house. Luke balances the rich young ruler (18:18–25) with wealthy Zacchaeus, whose restitution for this “white-collar crime” goes well beyond what would be expected. Jesus recognizes his faith-response and declares, “Today salvation has come to this house” (19:9). Luke affirms what we’ve already observed: “The Son of Man came to seek out and to save the lost” (19:9–10). Luke’s Jewish readers would hark back to another experience of salvation at Jericho. Hundreds of years before, it was Rahab, the harlot, who was rescued in the fall of her hometown (Joshua 6:22–25).

Once more, in this story, Luke highlights three of his common themes:

- The problem of wealth and how to deal with it

- Jesus’ investment in those known as “sinners”

- A faith-response to Jesus which leads to a new way of living

Luke 19:11–27: The Parable of the Pounds

On the journey to Jerusalem, Luke transitions from Zacchaeus’ stewardship commitment to Jesus’ kingly entry into the city with a parable involving both stewardship and kingship. Everyone hearing Jesus would know the story of how Herod the Great, who had a palace in Jericho, went to Rome to receive kingly rights (40 B.C.). Upon Herod’s death in 4 B.C., Archelaus, Herod’s son, also traveled to Rome to receive the right to rule Judea. In both cases, as in Jesus’ story, citizens opposed the quest to be king. So Jesus’ listeners get it when he launches his story with, “A nobleman went to a distant country to get royal power for himself and then return” (19:12).

Luke is probably reworking a similar story told in Matthew (Matthew 25:14–30). In that story, the departing, would-be king apportions a sum to be entrusted to each of 10 slaves. In Luke, the amount entrusted is less than Matthew’s version of the story, where “a talent” is equivalent to 15 years of a laborer’s wages. In Luke’s version, a pound — literally a mina — is still substantial, worth about three months’ wages for a laborer.

Having received royal power, the king returns and calls his servants to account for what they did with his money. Two servants did well with the master’s money, making a healthy profit. But a third merely hid the entrusted resources in a piece of cloth, for which he incurs the master’s judgment. In the next verse, the story shifts to those who had opposed the king, concluding with judgment declared against them as well (19:27).

King Jesus, Son of Israel’s God, is coming to Jerusalem. How will he be received there by his own people? This understanding of the parable plays out in the next days’ events. On the first Palm Sunday, many surely expected Jesus to take charge as Israel’s rightful king. But Jesus did not. His was not that kind of kingship. Others see this parable depicting the second and final return of King Jesus to his city and to his world, a return that we still await.

In either case, this is another heavy-duty story about accountability for our response to Jesus and our stewardship of resources placed at our disposal. As parable scholar Klyne Snodgrass concludes, “The issue is faithfulness in view of the present and future kingdom.” [Author’s Note 1] Then, Luke tells us, Jesus goes “up” — yes, uphill from Jericho, one of the lowest points on the earth — 17 miles to Jerusalem (19:28).

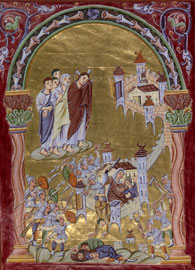

Luke 19:28–44: Jesus Enters Jerusalem

When contemporary pilgrims arrive at Jerusalem, they often do so via the Mount of Olives. After the long climb from Jericho, they crest a hill and celebrate the amazing city spread out before them across the narrow Kidron Valley. Today’s pilgrims pause at viewing platforms, where guides point out the city of David, the temple mount, and the glistening Dome of the Rock, sacred to Muslims, Jews, and Christians.

Jesus and his followers arrive at the Mount of Olives crest not on a tour bus, but on foot, with Jesus in the lead. It surely was a climactic moment 2,000 years ago. Jesus plans and stages the moment to communicate just the right message. Jesus’ entry into Jerusalem is a dramatic, acted-out claim to be ruler of the kingdom he’s been announcing from the beginning of his ministry. Disciples are sent to acquire a donkey’s colt for Jesus to ride. Good Jews knew the prophecy of Zechariah 9:9:

Rejoice greatly, O daughter Zion! Shout aloud, O daughter Jerusalem! Lo, your king comes to you; triumphant and victorious is he, humble and riding on a donkey, on a colt, the foal of a donkey.

Passover pilgrims join with Jesus’ followers to honor one who is obviously fulfilling messianic prophecy. They sing from Psalm 118, a song pilgrims sang on their way into Jerusalem. “Blessed is the one who comes in the name of the Lord” (Psalm 118:26).

Yes, there are grumblers who complain about the royal and messianic celebration. But Jesus responds, “I tell you, if these were silent, the stones would shout out” (19:39–40). Grumbling religious leaders are not new in Luke’s story, and do not surprise us. But what happens next, recorded only in Luke, does surprise us: “As he came near and saw the city, he wept over it” (19:41).

Tears were not foreign to Jesus. John’s gospel depicts Jesus weeping at the grave of a friend. “Jesus wept” is the shortest verse in the English Bible, but one of the most profound (John 11:35). Here, Jesus is weeping not for himself — though his death is only days away — but rather for the city, knowing what a terrible fate awaits it. Jesus, incarnate Son of God, weeps with those who have lost a loved one and weeps over a city full of people who will face the consequences of rejecting him.

Along with his tears, Jesus uses phrases and images from Old Testament prophets to describe what would come some 40 years later in A.D. 70, when Romans would besiege and destroy Jerusalem. Further destruction would take place after another Jewish revolt in A.D. 135. All this, Jesus declares, is “because you did not recognize the time of your visitation from God” (19:44). God visiting God’s people is a common Old Testament theme. Because people do not recognize this visitation by Jesus, there will be destruction and disaster. So Jesus weeps over his city.

Luke 19:45–20:19: Teaching in the Temple

Arriving in the temple, Jesus teaches in three ways:

- Jesus acts out who he is by cleansing his temple — “my house,” as he calls it (19:45–46).

- In response to angry questions about the source of his authority, Jesus puts the ball in the religious leaders’ court. And, since they are unwilling to commit to either the divine or the human origin of John’s baptism, Jesus refuses to answer by what authority he has cleansed the temple (20:1–8).

- He tells one more parable against “the scribes and chief priests” that triggers their desire “to lay hands on him” (20:19). In the story, God is the vineyard owner, Israel the vineyard, and its leaders the tenant farmers. The owner’s effort to acquire what is his from tenant farmers is unsuccessful. In a last-ditch effort to get their attention, the owner sends in his very own son. The wicked tenant farmers kill the son. The parable’s closing statement, that the owner will now destroy the tenants and give the vineyard to others, leads to the horrified listeners’ exclamation, “Heaven forbid!” (20:9–16). In parable form, this describes what is happening with Jesus in Jerusalem.

Luke 20:20–21:4: Disputing With Religious Leaders

Tension continues to mount between Jesus and the scribes and chief priests. Trick questions by the seemingly sincere are an effort by the leaders to trap Jesus in what he says. They focus on two sticky issues:

- Taxes (20:20–26).Should they be paid to the hated Roman overlords? If Jesus says “Yes,” he offends the people; if “No,” he’s in trouble with the Romans. But Jesus turns the tables on his questioners with a question of his own. “Show me a denarius. Whose head and whose title does it bear?”Answer: “The emperor’s.””Then give to the emperor the things that are the emperor’s,” concludes Jesus, “and to God the things that are God’s.”

- Marriage and the resurrection (20:34–40). In the resurrection, to which husband will a woman who has been married to more than one man belong? Jesus answers by making two claims:

Then Jesus goes on the offensive and asks a theological question about Messiah as David’s Son (20:41–44) and attacks the hypocrisy of religious leaders. He points to a widow who, out of her poverty, gives an offering. Her offering, says Jesus, is worth more to God than large, ostentatiously given offerings from the wealthy.

Luke 21: Signs of the End

Before tension and conflict build to decisive and violent action, Jesus offers an extensive teaching, most of which is found also in Mark 12 and 13. The teaching centers on the temple and what will happen to it.

The Jewish temple occupied a central place in Israel’s national life, but the temple had also come to stand for what Jesus opposed. And the temple would be destroyed. (Imagine someone prophesying that the Washington Monument or the Capitol Building would be destroyed!) In fact, the destruction of the temple and the city would be part of international, even cosmic convulsions (21:25–33).

In the midst of upheaval, kingdom-of-God people should “Be on guard … .Be alert at all times, praying ….” (21:34–36). Be patient and be steadfast in the midst of what God is doing, even in the midst of international upheaval.

Questions for Further Reflection

- Reflect again on the meaning of faith, as exhibited by the blind man and by Zacchaeus.

How is this different from common understandings of faith? What are you learning about saving faith? - In what areas of life are you living with a sense of accountability to God for resources placed at your disposal? How do you see yourself in the parable of the pounds?

- Imagine Jesus weeping over our cities today. Why might he do so? How do you respond to this picture of Jesus in tears?

- How do you see the depiction of international and cosmic upheaval lived out not only in the first century, but also in the 21st?

<<Previous Lectio Back to Luke Next Lectio>>

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons License.