Joshua/Judges Week 4

“Your Going Out And Your Coming In”: Joshua 3:1–4:24

Assistant Professor of New Testament, George Fox University

Read this week’s Scripture: Joshua 3:1–4:24

15:22

EnlargeIntroduction

EnlargeIntroduction

Psalm 121 is one of the shortest psalms in the Psalter — a mere eight verses — yet it succinctly relates how Israel is meant to view its covenantal God:

- When I look up to the “hills,” I know my helper (who made heaven and earth) is ready to move, ready to aid (121:1–2).

- You cannot catch him off guard, because he doesn’t sleep (121:3–4).

- Nothing will get to you of which he is unaware; his plan for protecting his people cannot be thwarted (121:5–7).

- The last line, climactically, says what all Israel needs to know: “The LORD will keep your going out and your coming in from this time on and forevermore.“ (121:8)

The idea of YHWH’s keeping watch over Israel in her “going out” and her “coming in” is probably meant to be a merism — a figure of speech in which two contrasting parts are used to encompass the whole. So, for example, when we read in Psalm 78, “May he have dominion from sea to sea,” it means “from one sea to the next, and everything in between.” The same goes for his watching over the “going out” and “coming in” that extends to wherever Israel may be at any time.

However, I think this psalmist’s statement is striking, because it represents well the connection between the unique events of the “Exodus” (the going out from slavery in Egypt) and the entrance into Canaan (the coming into the land of promise, where the LORD called them to rule and be a light to nations).

The glue that binds these two major events in the life of Israel is the guidance and protection of the LORD — who, just as the psalmist confirms, promises to be with his people; he reminds Joshua and his people two times in the book of Joshua, “I will be with you” (Joshua 1:5; 3:7).

Joshua 3:1–4:24, then, underscores the official step of “coming into the land” under the supervision of YHWH. There are two key parts to the story of the entrance into the land of Canaan. Joshua 3:1–17 narrates the miraculous crossing of the Jordan River, while Joshua 4:1–24 recounts the command of God that the people set up a memorial to commemorate this critical juncture in the life of Israel.

No Need for Dramamine!

Many interpreters of Joshua believe that the story of the crossing of the Jordan by Israel is the most important event in the book. Why is it so critical for the story? Let’s pause and jump to the end of the Bible for a moment.

In the book of Revelation, we are given a vision of the world at the end of the ages — what life will be like in God’s glorious eternity (Revelation 21:1–18). Streets of gold. Bejeweled walls. No sea …. Wait a minute. No sea? What does God have against the sea? Well, certainly he has no problem with water — it was used for rituals of cleansing and, eventually, connected to the Holy Spirit and new birth.

Nevertheless, in the ancient world, large bodies of water were sometimes viewed as symbols of chaos and evil. From the very beginning of the Bible — Genesis 1:2 — God separated the dark dome of “waters,” bringing order to chaos. We are told that Leviathan (yes, the sea monster) “frolics” in the murky sea (Psalm 104:26). Sea storms torment and sometimes kill sailors (Psalm 107; Jonah 1; Acts 27).

Remember, also, that when God grieved over humanity’s wickedness and decided to destroy the earth, he chose a flood of water as the means (Genesis 7), as if to bring chaos to bear again on earth, virtually undoing his act of ordering.

So when the Israelites stood before the Jordan River, which was positioned between them and the land “given” to them by their God, it was not a matter to take lightly. In fact, a close reading of Joshua 3 should cause the reader to make some key connections between the crossing of the Jordan and the famous parting of the Red Sea (as Israel fled from Egypt into the wilderness).

At the initial steps of the people of Israel into the Jordan, we are told that “the waters flowing from above stood still, rising up in a single heap” and that Israel was able to cross “on dry ground” (3:16–17; also 3:13). This language matches almost exactly the language of the Red Sea crossing (Exodus 14:16, 22, 29; 15:8, 9; see Psalm 78:13). As Israel looked back on these two key events, it was as if the seas, seen as the personification and embodiment of evil, had been conquered by YHWH:

When Israel went out from Egypt … Judah became God’s sanctuary, Israel his dominion. The [Red] sea looked and fled; Jordan turned back …Why is it, O sea, that you flee? O Jordan, that you turn back? …Tremble, O earth, at the presence of the LORD (Psalm 114).

There is another important connection to make. When Israel saw the “dry ground” appearing when the waters were divided, this may have made them think of God’s work of creation when he made dry land appear out of the watery abyss (Genesis 1:9). What would that communicate? In view of Israel’s marching into the land occupied by another group of people, it was a reminder, I am sure, that the God who is guiding them is the one God of the whole world, the creator of heaven and earth. Or, put another way, the God who “makes” (the seemingly uncontrollable sea as well as the land) is the same God who will “make” a way for his people.

The Jordan River became famous, after this threshold event for Israel, as a place where God did important and miraculous things:

- According to 2 Kings 5:10–14, the prophet Elisha sent Namaan to the Jordan to wash seven times in it and be healed from his leprosy — and he was!

- Elisha’s mentor, Elijah, was miraculously taken up into heaven at the foot of the Jordan (2 Kings 2:11).

- As recounted in the New Testament, the prophetic precursor to Jesus, John the Baptist, chose the Jordan as the special site where he would launch a renewal movement of repentance, hoping for God to act again in a powerful way as he had in olden times.

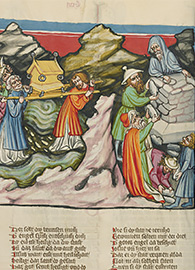

The Ark of the Covenant

When the LORD had promised to be with his people — unlike the time of the wilderness journey to Mount Sinai — his presence wasn’t represented primarily in a fire or cloud. Israel carried the “ark of the covenant,” a special “box” that contained the Ten Commandments, remnant portions of the manna from heaven, and Aaron’s budding rod (see Numbers 17:1–11).

More importantly, though, Israel believed that the invisible LORD somehow was enthroned on the ark (see 1 Samuel 4:4; 2 Samuel 6:2). That does not mean that the Ark of the Covenant was an idol — it was not in the shape of YHWH (as he has no form), nor did the Israelites believe that he lived exclusively in or around this container. And idolatry, of course, was strictly forbidden.

However, in some special way, he was with his people with this ark. It was like the travel-vehicle of the LORD. The LORD was meant to go ahead of his people symbolically in this manner and lead the way beyond the Jordan.

It was not the bravest and strongest warriors who were sent first. It was the priests who carried the ark (3:6). In 3:4, we are told that the ark and the priests were supposed to go ahead of the rest of the people and they were to maintain a distance of two thousand cubits — that’s over half a mile!

The nature of the crossing of the Jordan, then, underscores two key points.

- First, it was not going to be a normal fording of a river. This was going to be unique, because God was going to be with his people and pave their way — almost literally!

- Second, this initial miracle was meant to be a sign that Israel’s God was the living God (3:10). The gods of the others nations were considered by Israel to be false and dead. They were dead because they could not follow through with their promises. On the other hand, YHWH claimed to be the living God, LORD of all the earth (3:11), who could prove that he was able to save (remember what Joshua’s name means?).

The 12 Stones of Gilgal

At the church that my family attends, we partake of the Eucharist every Sunday — that sacramental institution where you take bread and wine and “commune” with the LORD Jesus Christ. Why? Because he told us to. We are told by Luke and Paul that Jesus instructed his disciples to take the bread and wine as his body and blood “in remembrance of me” (Luke 22:19; 1 Corinthians 11:24).

I am sure Jesus set up this memorial institution because we are a forgetting people. In the famous hymn, Come Thou Fount, there is the memorable line: “Here I raise my Ebenezer, hither by thy help I’ve come.” Who is Ebenezer and why did God raise him? Actually, “Ebenezer” is not a who, it is a what. In 1 Samuel 7:1–12, we are told that the Israelites were able to overcome the Philistines in battle thanks only to God’s miraculous intervention.

So “Samuel took a stone and set it up between Mizpah and Jeshanah, and named it Ebenezer [which means the ‘stone of help’]” (7:12). Sometimes we need to carry out tangible acts of remembrance that give us a chance, later on in times of adversity and difficulty, to call to mind those works of God that teach us that he is present, he is loving, and he is strong.

In Joshua 4:1–24, a representative from each of the 12 tribes was called up to take a stone from the dry ground of the middle of the Jordan (as they were crossing) and set it up in the place where they camped on the other side (Gilgal). This is significant for several reasons.

- The fact that these were 12 stones carried by 12 people was meant to be a sign of the “diverse unity” of the people — each group was important in its distinctiveness, and all worked together as one with the LORD’s help.

- There is an important pedagogical element to this memorial that was built. Assuming that Israel was going to successfully take over the land and have it for eternity, naturally children of future generations would see the stones and ask about them. Israel had the responsibility of teaching her children to recognize and pass on the mighty acts of the LORD, who could make the Jordan’s mighty waters stand still (4:6, 21).

- The “sign” (4:6) that the memorial represents is not only for the Israelites, but also a testimony to the world, “so that all the peoples of the earth may know that the hand of the LORD is mighty” (4:24). Certainly the fame of Israel’s God and his power reached Jericho, as Rahab already knew of the military might and miraculous events that attended Israel.

Reflections

Whenever my students comment that the Old Testament is dull or irrelevant, I am drawn to passages like Joshua 3–4 and I wonder how students react to these stories. As for Joshua 3, like Israel, we are constantly standing before great adversities and tumultuous rivers of decision and thresholds of the stages of our lives.

What does it mean to send the “ark” ahead of us? What does it mean to trust the God who stops mighty waters? Are there times when we think that he is our local God and forget that he is LORD over all — even the darkest, scariest, ugliest sectors of life? Dare we “sanctify” ourselves (3:5), carry out his presence into the world, and take hold of his promises?

What about the important act of remembering? Christians today, especially of the younger generations, are quite skeptical of institutions and rituals — “organized religion” is on the decline. We would rather be individuals who worship privately and without ritualistic actions.

That might be fine, except that Scripture reminds us (!) that we are a forgetting people. Stones need to be built for the same reason that Microsoft Outlook bleeps 15 minutes before a meeting that I would probably miss if I did not have that attention-getting device. For the same reason, my dentist’s office sends me an automated phone call the day before my appointment.

Whether it is celebrating Advent, baptizing a new believer, partaking of the loaf and the cup, or just lumping rocks together, there is nothing wrong with carrying out bodily, tangible expressions to remember something important; it is not different from celebrating an anniversary or birthday.

What can we do today, what sorts of things can we make, build, design, record, inscribe, and create, that will help our children, and their children, to remember the great things the LORD has done for us in our time and in times before us? Think about it.

Questions for Further Reflection

- Crossing the Jordan was a key transition in the life of Israel. It was a rite of passage, so to speak. What are some rite-of-passage kinds of experiences that you have been involved in (religious or otherwise)? Was that experience important to you?

- The Lectio writer connects this key event of crossing the Jordan to the similar event of the parting and crossing of the Red Sea. What is the significance of relating these two events?

- The Lectio writer notes, “What does it mean to send the ‘ark’ ahead of us? What does it mean to trust God who stops mighty waters? Are there times when we think that he is our local God and forget that he is Lord over all — even the darkest, scariest, ugliest sectors of life? Dare we ‘sanctify’ ourselves (3:5), carry out his presence into the world, and take hold of his promises?” How might you answer these questions? What specific areas of your life today are challenged by this call to trust in God’s powerful presence?

- In terms of Israel setting up memorial stones, how can our faith communities better invest in remembering what God has done in the past? What does your faith community currently do? Are there special moments in your life where God has worked graciously and powerfully that you can and should commemorate? What might it look like to set up a memorial as an encouragement both now and to future generations?

<<Previous Lectio Back to Joshua/Judges Next Lectio>>

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons License.

Thanks for this concrete and applicable material. I especially valued your linkage of Psalm 121 with Joshua. That psalm is one of my favorites, and one I use when I take a group on a long journey. I am glad you and your family thrive on the weekly communion at FFMC.

HMA

Whenever I participate in communion I am awestruck that I am standing in a 2000 year old river of believers. May we never be a “forgetting people”!

Thank you Dr. Gupta for the reminder.

Amen and amen.

I have to say thank you for this selection of word. For this was that reminder of the True Fast of how we must allow GOD to Be our rear guard and HIS RIGHTEOUSNESS TO GO BEFORE US in this case of waters the Lord was saying storms will come, and waves will blow but a STABLE MAN IN GOD WHO GROUNDED ALWAYS EXPECTS DELIVERANCE HOW EXCITING GLOOOOOOOOOOORY TO OUR GOD HOW AWESOME THANK YOU VERY MUCH. This has made my day and brought great joy.

Suprina: Glad to hear it! May God continue to reveal more of His character to you as you study Scripture!

I appreciated the connections that you made to Ps. 114. It helped me view this passage in a new way. A nice focus on God’s power and activity in the world.

Jerry, thanks for the note. God’s presence in our lives amid the going outs and the coming ins is indeed an immense blessing.

You presented God’s message with powerful impact. The “reflections” brings lots for me to think and remember throughout the day.

Excellently done study!

And a blessing as an encouragement to us as we are raising support to be missionaries in Africa.

Hi,

I like your examples of going out and coming in. I think the going out and coming in language is also part of the wider metaphor and cultural understanding in Israel of God as Shepherd and Israel as His sheep. Shepherds went out in the morning leading the sheep to pasture and still waters that they had scouted out in advance for their flocks. They protected the sheep all day leading them also to health and growth environments. They came in in the evening and waited till the last sheep was in the pen/fold before closing the gate/door. In some cases the shepherd actually slept at the door/gate to keep the sheep safe. Moses was a shepherd leader who took Israel out to pasture for forty years in the wilderness. Later Solomon asks for wisdom to go out and come in – before his people- shepherd language again. Of course David his father was literally a shepherd growing up, and one of Israels great shepherd leaders. Jeremiah reminds us of evil shepherds in Israel’s leadership who don’t know how to go out and come in appropriately ( ie. care for and lead) before the sheep unlike David and coming Messiah the true and good shepherds. Good stuff. Enjoyed the read.

Hey that’s a really neat correlation to shepherding. I came to this article because I was struck by Caleb’s use of the phrase ‘going out and coming in’ and wanted to dig down into what it really meant. So great comment, thanks!