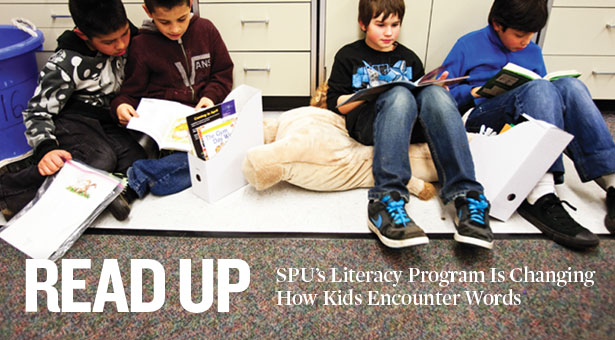

Third-grade students in Kathryn McGreenery’s class read independently and with buddies — they work together to practice fluency and comprehension skills.

Third-grade students in Kathryn McGreenery’s class read independently and with buddies — they work together to practice fluency and comprehension skills.

By Laura Onstot '03 | Photos by Mike Siegel

Kathryn McGreenery M.Ed. ’11 spends her days with 24 third-graders at College Place Elementary School in Edmonds, Washington.

Each year, more students arrive in her classroom below the standards for third-grade reading, including an increasing number of students who don’t speak English at home. “I have to differentiate the full range of students, some of whom are reading at a fifth-grade level and some of whom are learning letter names and sounds,” she says.

Though her undergraduate education had given her the tools she needed to teach in most areas, she says she was struggling to teach literacy skills to a wide range of readers.

“Everybody knows that vocabulary is important,” says Bill Nagy, a Seattle Pacific University professor of education who specializes in literacy, “they often just don’t know how to teach it.” Nagy didn’t plan a career turning teachers into masters of literacy. Language itself was his primary interest in the ’70s as he finished a doctorate in linguistics and, a few years later, landed a research position at The Center for the Study of Reading at the University of Illinois. There, he found fellow academics trying to determine the best way to help kids learn to read.

“It was a time of great ferment,” Nagy says now. “How to teach reading has been a hotly debated issue for the last 30 or 40 years.”

Teacher Kathryn McGreenery works with a small group of students who need additional support with reading comprehension skills, such as identifying main ideas and supporting details in a text.

Teacher Kathryn McGreenery works with a small group of students who need additional support with reading comprehension skills, such as identifying main ideas and supporting details in a text.

Nagy hoped to move beyond ideological debates to carefully researched instruction methods — no easy task. “Teaching a classroom of children is more complicated than putting a rocket on the moon, as far as I’m concerned,” he says.

At SPU since 1996, Nagy focuses on two things: helping teachers in the classroom through SPU’s Master of Education in Literacy program and advising doctoral students, the next generation of literacy researchers. For his literacy work, Nagy was inducted into the Reading Hall of Fame in 2009.

A lot of teachers face McGreenery’s struggle, he says, finding themselves ill-equipped to teach reading to kids from non-English-speaking families or with learning disabilities.

“The most vulnerable children are not being served by our educational system,” Nagy says. “I’ve come, increasingly, to see my work as addressing that.”

The Power of Words

While earning a master’s degree in literacy at SPU, McGreenery said she learned to rethink

the role of individual words in learning to read. McGreenery says she always knew vocabulary

was important, “but I didn’t see how incredibly impactful vocabulary (or lack of vocabulary)

was and how huge of a task it was to teach!”

For years, teachers have been having students memorize words and definitions, a method Nagy describes as “worse than a waste of time.”

“A lot of vocabulary activities in classrooms are just chances for kids who already know the words to show off and make kids who didn’t know the word already feel humiliated,” Nagy explains.

Instead, Nagy says teachers need to support kids so they can learn to use words meaningfully. As an example, Nagy says it’s best to think of learning to use vocabulary like learning to use a tool. The best way to master it is to do it.

Think of the word “confine,” Nagy says. Rather than having students parrot a memorized definition, he suggests the teacher ask students about things they might want to confine.

Nagy imagines a student named Johnny who replies, “My pet tarantula.”

“Why?” asks Nagy’s hypothetical teacher. “Because it might bite my little sister,” responds the student.

Not only is Johnny now starting to get a handle on the word “confine” but he understands that the concept of “confining” has the power to protect his little sister.

McGreenery says not only did she gain techniques for teaching vocabulary to improve literacy while studying at SPU, but she gained an appreciation for the rigorous commitment to research espoused by Nagy and the other faculty members.

“One thing I have come away with is the need to focus my instruction around research-based methods rather than unsubstantiated trends,” she says.

Better Teachers Through Research

Nicole Swedberg M.Ed. ’95, Ed.D. ’04, had been a first grade teacher for years when she started noticing a correlation between language development and literacy in her students. “I wanted to know more about this connection,” she says.

Swedberg started graduate work at another university, but transferred to SPU largely due to several conversations she’d had with Nagy. He had a different way of thinking, she says. “His perspective, although broad, tends to focus on the features of language itself, and how these features interact with strategies.”

Swedberg now works in a private practice helping struggling readers and writers, many of whom are dyslexic. One aspect of her work at Seattle Pacific that she uses almost constantly is what Nagy describes as giving students “a sense of task.”

She gets them to use words by writing text for pictures, using a book with images of frogs flying around a small town at night. “It’s a story that just wants to be told, and my students jump right into the telling,” Swedberg explains. “Everyone calls [Nagy] a rock star,” says Kristine Gritter, SPU assistant professor of curriculum and instruction. “He’s not just a scholar, he’s a top scholar.”

Literacy expert and Professor of Education Bill Nagy in his office at SPU.

Literacy expert and Professor of Education Bill Nagy in his office at SPU.

As a middle school language arts teacher in Florida, Gritter found herself frustrated by the lack of continuing education for teachers focused on improving their ability to teach basic skills such as reading. Some of her students were still struggling to read and she didn’t know how to help. “I didn’t know a lot about reading, I knew a lot about literature,” she says. Now Gritter trains teachers to help out struggling readers who fell through the cracks earlier in their education. “Many secondary English teachers are not aware that adolescents struggle with reading, what their struggles are, and how to deliver instruction that remediates some of the struggle,” she explains.

While Nagy focuses on developing reading skills, Scott Beers, chair of the master of education in literacy program and associate professor of curriculum and instruction, has been training teachers to use assessments to identify struggling readers early “before they fall so far behind that catching up is unlikely.”

Beers and Nagy are also partnering with the Center for Defining and Treating Specific Learning Disabilities in Written Language at the University of Washington on a just-awarded federal grant. The team, which includes education experts and neuroscientists, will identify and help students with learning disabilities that hinder their writing ability. “I believe that we will do work that will substantially improve teachers’ ability to help students,” Nagy says.

Rounding out the literacy faculty at SPU is Assistant Professor of Education Jorge Preciado, who researches ways to improve literacy teaching for students learning English, like those coming into McGreenery’s classes.

Literacy is essential to success in school and careers, and Nagy and his colleagues are determined to ensure that teachers like McGreenery and Swedberg are able to get their students writing and reading, no matter where they come from, what language they speak, or what learning challenges they might face.

A great book can get kids reading. Kristine Gritter, SPU assistant professor of curriculum and instruction, offers her recommendations of what may inspire yours.

Laura Onstot ’03 lives in Seattle and writes about everything from the city’s best donuts to national politics. Her work has appeared in Seattle Weekly, The Seattle Times, High Country News, MSN, AOL, The Rumpus, and Agence France Presse. When not at a keyboard, she can be found biking, hiking, and sailing the Pacific Northwest.