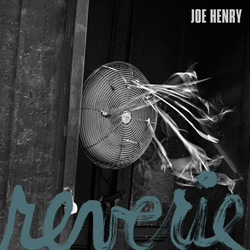

Joe Henry’s Reverie

An Album of Border Crossings and Meditations in the Dark

By Jeffrey Overstreet (jeffreyo@spu.edu)

"Everything is free now," Gillian Welch once prophesied.

And with recorded music, that’s almost true. As recordings become more and more accessible — streaming previews, music services like Napster and Spotify, YouTube concert bootlegs — the experience of live music seems to become more and more valuable. No matter what innovation we’ll find online tomorrow, nothing can equal the privilege of standing in the musician’s presence during a performance.

But on his 12th album, Reverie, Joe Henry gets about as close as possible to delivering the live experience to your living room, your car, or your headphones. Listen closely, and you’ll hear more than music. You’ll hear the rattle and hum of the gear, the room, and the environment around it.

A Grammy-award-winning producer of great artists like Allen Toussaint, Solomon Burke, Elvis Costello, Carolina Chocolate Drops, and Over the Rhine, Henry spends more time elevating other artists than performing music he composed himself. But his own songwriting can stand beside the best work of any artist he’s produced. And Reverie is his most spontaneous, immediate, intimate album.

You’ll hear that not only in the lyrics — which speak of personal experiences, epiphanies, doubts, and dreams — but also in the instrumentation, which he recorded in the basement recording studio of his historic South Pasadena home. (Henry lives in the Garfield House, which was built for President Andrew Garfield’s widow after he was assassinated.)

With the windows open to outside noise — a howling hound, a visitor, the wind — Henry draws together some of his finest collaborators. Jay Bellerose (drums), David Piltch (upright bass), Marc Ribot (guitar and National ukulele), Patrick Warren (pump organ), and others play so closely that you can almost hear the edges of their instruments bump against each other.

Thus, as boundaries between the instruments blur, so do the borders between the physical environment of their workspace and the haunted landscapes of Joe’s lyrical imagination. "I had to look back to see it," he said in an interview at Radio Times. "I think all of the characters in the songs are wrestling with an awareness of time passing." These are songs about border crossings — from summer to autumn, from dark memories to dreams, from the material into mystery, from the present into the past or the future.

In the album-opener, "Heaven’s Escape," he’s a character lying on the hood of a car and watching a film projected on the side of a building. Note: The building is a bank. So this wall divides dreams from what we now associate with corruption and failure. (That’s a perfect example of how Henry loads his lyrics.)

The film inspires a restlessness, an eagerness to escape into something new and better. "I feel I’m an angel in waiting," he sings, sensing "the promise of heaven" in that flickering light.

But as the song progresses, and the refrain — "Oh how, my love, will we escape?" — is repeated, we begin to realize that the singer is never going to be content. He sees any context as something insufficient, so that even in the final refrain, in a vision of a final, heavenly destination, he's feeling the urge to plan a prison break. The scene might remind you of the film The New World, in which the explorer John Smith leaves behind a paradise and an offer of true love because he cannot quench his wanderlust.

He delivers more indelible imagery in "Eyes Out for You" — a song in which a man compares his troubled state of mind to a caravan in which "dusty miners" are concealed and fearful of being caught. The man is on the run from the law, haunted by guilt and by the memory of someone who inspired his reckless flight. Determined to absolve himself, he makes up a story about his life and keeps running, leaving a path of destruction behind him. These scenes of a man driven to crime, denial, a violent conflagration, and a desperate escape recall the film Days of Heaven, or the apocalyptic stories of Cormac McCarthy — American parables resonant with Old Testament echoes.

But the imagery here isn’t always sharply focused. Sometimes, as on his last album, Blood from Stars, it’s more surreal and haunting, like figures moving beyond antique glass. Henry knows when he’s happened upon an evocative phrase, and he often repeats them, so that they increase and cast long shadows.

In that Radio Times interview, he described writing lyrics as a process that has more to do with discovery than design. "Sometimes it’s just a phrase that will speak itself into your mind, and it’s like seeing something shiny sticking out of the dirt, you know? If I dig in there, there might be nothing, there might be a whole bicycle down there, and I can ride away with it. But you don’t know until you start digging."

Henry’s a songwriter who wears his influences not on his sleeve, but in the soles of his shoes. As spontaneous as he sounds, he’s standing on a firm foundation of American rock, folk, and blues. And his lyrics are tapestries where you might tease out threads drawn from great literature. (He’s spoken reverently of Flannery O’Connor, Alice Munro, Rainer Maria Rilke, Raymond Carver, and Gabriel García Márquez.)

And yet, there’s never a sense of nostalgia or name-dropping. While every song bears the wisdom of time, they also speak to the here and now. Into days crowded with headlines about failing heroes and fraudulent leaders, Henry sings three stinging questions: "How do you like your blue-eyed boy?" "How do you hear your lion song?" and "How do you keep your time to come?"

Speaking of our "time to come," it sounds like there may not be much of that left. In fact, I would not have been surprised to find that Henry drew inspiration from Bob Dylan’s refrain "It’s not dark yet / But it’s getting there."

In "Dark Tears," death makes an ominous appearance: "Out along the darkest bank, I can see your boat from here …" Even songs about building and beginning are burdened with a sense of the lateness of things. "Here begins the fitting end / To what we’d started over— / When tomorrow is October …"

In "Room at Arles," the first time Henry has recorded himself solo with acoustic guitar, sadness and celebration mingle in memory of the late Vic Chesnutt, an imaginative and evocative songwriter who committed suicide last Christmas. The song rightfully implies that both artists — the singer and the song’s subject — have always worked with the sense that departure is imminent: "Every song I’ve ever sung / Has been a song for going …"

But it’s not a bleak or hopeless vision. The music itself — sometimes playful, sometimes scary, sometimes rowdy with celebration — redeems the most disturbing sentiments, reminding us of beauty even in the darkest places. And there’s a reverence in the performers’ restraint, pregnancy in their pauses, as if something entirely new is about to unfold. In Odetta, Henry sings,

Nothing is now as it appears

And there is no law speaks to that,

Just an ocean’s roar between my ears

And down here deep inside my hat

Where broken ships still drift and pine

For some new world reverie …

As the world darkens, we may arrive at our destination, but that’s not necessarily the end. Sam Phillips sang, "Help is coming / Help is coming / One day late." In a similar fashion, Joe Henry sings of a future beyond the end, a meeting after the arrival:

I’m an hour from arriving,

Three from where I rose to go —

And maybe two from where I’ll find you,

Between the world and all I know.

It has the glow of deep consolation, a glimpse of a glorious reunion seen as through a glass … darkly.