How to View a Work of Visual Art

By Katie Kresser, SPU Assistant Professor of Art History

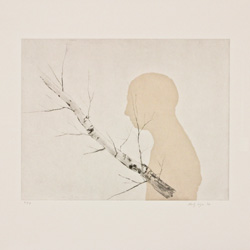

Enrique Martinez Celaya, "Figure With Birch," Color Aquatint Etching With Drypoint, 22 × 25, 2002. This and other prints will be on display in the show Still Small Voice: Selections From the Northwest Nazarene University Friesen Print Collection, October 10-November 22, 2011, in the SPU Art Center Gallery.

Enrique Martinez Celaya, "Figure With Birch," Color Aquatint Etching With Drypoint, 22 × 25, 2002. This and other prints will be on display in the show Still Small Voice: Selections From the Northwest Nazarene University Friesen Print Collection, October 10-November 22, 2011, in the SPU Art Center Gallery.

Most of us know a little bit about visual art. Perhaps we've heard of a few famous paintings, like Leonardo da Vinci's "Mona Lisa." But what makes a great work great? How do we know what to look for? What, in short, is the best way to approach a work of art?

Many artists believe that certain forms and colors evoke certain emotions. Think, for a moment, about major and minor keys in music. In the same way that major keys feel happy and minor keys feel sad, the forms and colors in art can speak to our emotions.

As you approach a work of art, think about how the forms make you feel. Do you feel darkness and sadness? Lightness and joy? Mystery? Chaos? Delight?

Works of art draw us in with their visual music. But once we get closer, we notice the subject matter: landscapes, or dancers, or battles, or flowers. It's tempting, sometimes, to "read" an artwork's subject matter without thinking about the visual music that attracted us in the first place. But we must remember that forms and stories go hand in hand! Visual art is special for the way it takes stories and makes them come alive for the senses. As we "read" a picture, we must be sure to think about how the visual music accompanies the story, making it emotional, dynamic, and distinctive — making it come alive.

The picture here, a print by the Puerto Rican artist Enrique Martinez Celaya, draws us in with soft colors and simple forms. From a distance we see a rose-colored vertical expanse and a gray diagonal, making a beautiful design. Attracted by the gentleness and subtlety of the image, we come closer to see the silhouette of a man and the naked branch of a birch tree. The delicacy of the colors and lines makes us sympathetic toward these figures. We feel for the man — faceless and nameless – and we wonder if he is something like this tree. To engage with this image, we must approach it slowly, letting it wash over us.