Web Feature Posted March 18, 2011

What the Oscars Overlooked

By Jeffrey Overstreet (jeffreyo@spu.edu)

Toy Story 3, courtesy of Disney/Pixar.

The Oscars are over. The winners took their awards home, and the losers smiled bravely while the cameras flashed.

You may have already forgotten who won the big awards. There’s no shame in that. The Academy Awards are always tainted by the prioritization of popularity, money, and celebrity. They fail to help us discern which of these films, if any, are timeless, meaningful, influential works of art. In most cases, we won’t have a sense of that until years — even decades — later.

But the 10 features nominated for Best Picture in 2010 were all commendable for one reason or another. Let’s revisit them, and observe what Oscar didn’t invite us to consider: the questions they raise and the challenges they pose to us. Each one serves as a sort of parable, offering frightful glimpses of the wages of sin or inspiring pictures of virtue and hope.

I’ll proceed in the order of my preference — saving my favorite for last.

10. Black Swan: Would You Strive to Succeed at Any Cost?

If we summed up the central lesson of most American entertainment, it would probably be something like this: “Just do it — follow your heart, no matter what it costs you. Don’t let anybody tell you what you can or cannot do.”

The myth of “Swan Lake” is one of those cautionary tales that adds a necessary corrective to this notion. Our hearts are not perfect. They’re often vain, self-serving, and deceitful. They can lead us into self-destructive behavior.

Black Swan, Darren Aronofsky’s film about a “Swan Lake” dancer’s self-destructive egomania, reminds us that if we pursue our dreams without humility and love, we’re doing harm to ourselves and everybody else.

Oscar-winner Natalie Portman brings impressive passion and physicality to the role of Nina, the ambitious young dancer who dreams of being a star. Mila Kunis is equally good, if not better, as Lily, the dancer who Nina sees as a rival. When they share the screen, Nina seems to be suffocating with fear, while Lily becomes magnetic, warm, and appealing. It’s clear that this won’t end well.

Nina is clearly self-absorbed, greedy, and paranoid. Thus the film becomes something of a study in the side effects of selfish ambition. And yet, there’s nothing particularly thought-provoking here. We know in the first 10 minutes that Nina is sick in the head. For another 90 minutes, we watch her falling to pieces in a series of horror-flick jolts and psychological thriller clichés. It’s all so frantic, it can distract us from the fact that the dialogue is unnecessarily banal, as if there were no real script at all.

Aronofsky has the talents of a great artist, but he’s also an adrenaline junkie. He goes for violent energy over poetry, shock over suggestion, emotion over intelligence. Black Swan stirs up a cyclone of horror clichés and melodramatic flourishes into sound and fury that signifies, in the end, very little.

Inception, courtesy of Warner Brothers Pictures.

Inception, courtesy of Warner Brothers Pictures.

9. Inception: Are You Living in a Manufactured Dream, or Facing the Hard, Real World?

Against all odds, Inception — one of 2010’s most intellectually challenging movies — became a blockbuster.

How did that happen? Its mind-bending premise was so intriguing, word of mouth spread. Everybody wanted to ponder the puzzle. But the film was also helped by its young and appealing cast (Leonardo DiCaprio, Joseph Gordon-Levitt, Tom Hardy, Ellen Page, and veteran Michael Caine), and its thrilling effects.

And yet, I doubt that the film is ever going to become something more than a rush of “cool.” Does it reach our hearts? I don’t think so. The film’s own multilayered structure keeps us so busy scrambling to follow the narrative that the central character’s moral dilemmas and personal pain barely have a chance to register in our attention. These undeveloped characters make the characters in other Christopher Nolan films — The Dark Knight, The Prestige, Memento — seem complex and full of nuance.

And that’s to say nothing of the film’s seeming disinterest in the ethical dilemmas of the “inception” process. Shouldn’t a film about invading other people’s brains and planting ideas there pause to consider that this is a sort of psychological rape? Their goal might be desirable — the breakup of a corporate monopoly — but Cobb and company behave so unethically, I wanted them to fail.

Still, there are some good ideas worth discussing here. We spend our days absorbing advertising in all kinds of forms. Advertising is designed to “implant” ideas that will affect our behavior. In what other ways are our behaviors influenced by outside forces? In what ways are we living in a “manufactured” world that keeps us from engaging with the lives and needs of others?

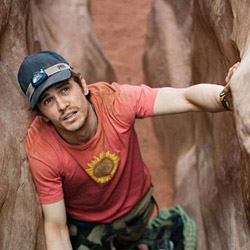

127 Hours, courtesy of Fox Searchlight Pictures.

127 Hours, courtesy of Fox Searchlight Pictures.

8. 127 Hours: What’s the Immovable Boulder in Your Life?

Imagine falling into a crack in the earth, and getting trapped there for several days, your arm pinned by an immovable boulder. Such a calamity would probably test your faith. Would you question the existence of God? Cry out to him? Give up on him?

Danny Boyle’s film about Aron Ralston’s ordeal is supposed to be about the long hours of the climber’s struggle for survival while stuck in Utah’s Blue John Canyon. During his desperate circumstances, we see Ralston wrestle with regret and yearn to connect with his family and friends. But does the film take us any deeper than that?

All of Aron’s tangential hallucinations and dream sequences seem designed to help us arrive at simple and predictable conclusions: That Aron shouldn’t be so reckless in his independence, and that, yes, he does need other people. His need for any kind of spiritual consolation remains curiously ignored. What does he believe? We don’t know. Who is he addressing when he moans, “Please … please ….” Who does he thank when things take a turn for the better? We’re not told.

Meanwhile, Boyle’s movie is anything but stuck. It’s what we’ve come to expect from him — a whirlwind of hyperactive cinema. Could a film about being trapped in a crevasse be any more acrobatic than this one?

That’s a shame. James Franco appears to be giving a great performance, but Boyle splices and dices his footage so relentlessly that we only experience fleeting moments of Franco’s work.

In this sense, Boyle’s film reminds me of Darren Aronofsky’s Oscar entry: Black Swan. The directors seem worried that they’ll lose our attention. They’ve made movies that are closer to an amusement park thrill rides than meditations on human nature, suffering, and the consequences of misguided priorities. The primary substance of both films is their style; their subjects get a little lost. It’s an ordeal for the audience, but it’s the wrong kind of ordeal. It becomes a test of nerves, rather than a challenge for the body and the soul.

For a great film about what goes on in the human head and heart during an ordeal like this, rent Touching the Void instead.

7. The Fighter: What Does It Take to Make Us Reach Across the Table?

David O. Russell’s take on the true story of the unlikely welterweight boxing champion "Irish" Micky Ward and his half-brother Dicky, an ex-con and a junkie, drew us into scenes of ferocious family drama.

I had to wonder if Micky’s technique in the ring — holding back, taking a long beating, and then fighting back with a sudden strong strike — was a method he learned while trying to cope with his relentless family members. Micky, Dicky, their seven frightening sisters, and their overbearing mother clashed with such violent energy that the film’s boxing scenes seemed almost docile by comparison.

The Fighter’s depiction of the sordid culture that surrounds boxing made it difficult for me to feel much hope for the family’s mental, physical, and spiritual health. Boxing can be — and usually is — devastating to the body and the brain. And the greed and corruption in the world of that sport rarely leave anyone uninjured. While the crowd cheered for Micky’s climactic fight, I wanted to see someone come along and rescue the whole family from a world of destructive influences.

The performances in this film are utterly persuasive and impressive: Mark Wahlberg, Christian Bale, Melissa Leo, and Amy Adams all deserved awards.

And the film, for all of its noise and violence, delivers a knockout punch to the heart near its predictable conclusion. We know the film is taking us on a familiar journey toward a championship fight. But what we don’t know is that it will deliver a moving illustration of humility, compromise, and reconciliation.

In that sense, The Fighter reminds me of The Rookie, another sports movie that tugged at the heartstrings and inspired us to become people of character.

6. The Kids Are All Right: What Does Love Require of a Family?

Annette Bening, Julianne Moore, and Mark Ruffalo turn in excellent performances in Lisa Cholodenko’s family drama. The characters they bring to life are intense, they’re funny, they’re awkward, and they’re very, very complicated.

The issues at the heart of the movie are complicated too.

This is a film about Jules (Julianne Moore) and Nic (Annette Bening), a lesbian couple who are raising two children together. But it’s also about the longings that those children, Joni (Mia Wasikowska) and Laser (Josh Hutcherson), feel for the missing piece in their lives — a father.

It’s interesting to me that these children are so intent on meeting their biological father (played with roguish charm by Mark Ruffalo). It seems they are more than merely curious. They feel a powerful attraction to him, wanting some kind of ongoing relationship. Something in them wants — no, needs — a father, as if the biological connection might be meaningful even if there has never been a relationship beyond that.

Every family is broken. Even though none of us experience something that is ideal, we all long for those missing pieces. It’s as if there was a kind of family that was meant to be. We all have built-in longings for mothers and fathers. And even more, we all have a built-in expectation of love. If we don’t find it where we should, we go looking elsewhere.

Wasikowska and Hutcherson give admirably understated performances, inviting us to sympathize with them as they try to make sense of their disordered childhoods. What is more, Bening, Moore, and Ruffalo all create convincing, charismatic characters who are needy, passionate, funny, and sad.

The Kids Are All Right reminds us that while this fractured world’s families come in all shapes and sizes, some things never change. A child’s life is shaped by love, or the lack of it. And a parent’s most important responsibility is to fill the home with unconditional love, knowing that every choice will make a difference as children watch, learn, and grow. The film’s broken heart is exposed most powerfully when a child confronts an irresponsible parent and says, “Why couldn’t you be … better!”

5. The King’s Speech: Do You Have the Courage of a King, or the Patience of a Teacher?

The big winner on Oscar night was a film that made audiences feel good. It showcased three excellent actors — Colin Firth, Geoffrey Rush, and Helena Bonham Carter — in appealing performances. It was handsomely staged, and written with wit and eloquence. And it was an inspiring “You can do it!” story.

King George IV’s seemingly unshakeable stammer — like Aron Ralston’s seemingly immovable boulder — becomes symbolic for each moviegoer of whatever in his or her life has become an obstacle, an insurmountable challenge. The movie kindles within us the desire to see the impossible made possible. “Bertie” will, for the sake of his wife and his country, wrestle his fears and find his voice.

But Tom Hooper’s movie is also about the qualities of a good teacher. Or, in this case, a great teacher.

As the spluttering Bertie becomes a volcano of frustration during his speech exercises, his therapist Lionel Logue is a picture of perseverance. With good humor, infinite patience, and inspiring compassion, he reminds us that a great teacher looks, listens to, and loves his student.

Now, did The King’s Speech deserve all of those Oscars? Will it sustain a reputation as the finest cinematic work of 2010?

That’s unlikely. Even though Tom Hooper took home a Best Director award, it’s hard to see any distinct directorial vision in his work. And the film lacks the sort of indelible imagery that makes classic movies linger in our memories.

But if you win hearts, you win enthusiasm. And if you win enthusiasm at just the right time, you win Academy votes. The King’s Speech won eight golden statuettes on Oscar night. And while many discerning critics may object, it’s hard to get upset over America’s love for a movie about the fine art of teaching.

4. The Social Network: What If You “Friended” the Whole World, but Lost Your Soul?

Zuckerberg, Zuckerberg, Zuckerberg.

The programming genius who invented Facebook seems to be the only character who gets much attention in conversations about David Fincher’s film The Social Network. Jesse Eisenberg’s performance as the ambitious young visionary earned him an Oscar nomination, and the film’s sophisticated script — which portrays him as quick-witted and motor-mouthed — made it a Best Picture pick for many pre-Oscars guessers.

But is Mark Zuckerberg really the center of this film?

This audacious super-student who wanted to get into elite clubs makes quite a subject. But the film is also about Zuckerberg’s business partner, Eduardo Saverin. Saverin gets caught up in the rush of Facebook’s juggernaut success, only to realize that success is sucking the life out of his friendship with Zuckerberg. It’s also leading him into a world of business in which words like “loyalty” and “ethics” are fantasies.

If the audience sympathizes with anybody in this movie, it’s probably Saverin. And Andrew Garfield’s performance anchors Saverin as the film’s true, broken heart. He’s the one who wants to believe that good business can be done without sacrificing conscience.

While screenwriter Aaron Sorkin’s narrative is far too fictional to be taken as an accurate account of the Facebook story, it is remarkable in how it challenges the values that are driving not only the Internet but the whole engine of capitalism.

Zuckerberg is not so much a villain as a product of consumer culture. For him, the goal is to prove himself as the best in his field, no matter what it costs him along the way. The emptiness of Zuckerberg’s life at the film’s conclusion, not unlike the emptiness experienced by the amoral antiheroes in so many Woody Allen films, is what lingers … a haunting sense that while he has gained “the whole world,” he has given up his soul.

Meanwhile, Saverin remains on the sidelines, wounded and betrayed, but clinging to the shreds of his dignity. His loss may give viewers a vision for another way of doing business.

3. Winter’s Bone: We Believe in the Kingdom Come, But How Do We Survive Until Then?

When death has come and taken our loved ones,

It leaves our home so lonely and drear …

Those lines from an old gospel song are sung in Winter’s Bone, Debra Granik’s harrowing adaptation of the Daniel Woodrell novel. They echo the plight of the film’s young heroine, Ree Dolly, a troubled 17-year-old “bred and buttered” in the Ozark mountains, and left to raise her younger siblings while her father is jailed for dealing meth and her mother sits in a traumatized state.

Then do we wonder why others prosper

Living so wicked year after year … .

In a wilderness of poverty and drug addiction, Ree is trying to stay clean, trying to keep her family from sinking beneath the evil that saturates the woods. In a searing debut performance, Jennifer Lawrence makes us care about Ree. Indeed, by the conclusion, we admire her ferocity, her dedication, her willingness to put her life on the line for those who depend on her.

Winter’s Bone is never predictable. A hero might be an abusive husband, a meth addict, and a man willing to threaten a policeman. But nothing is black-and-white in these wicked woods. In time, we’re grateful for Ree’s uncle, a volatile, dangerous man called Teardrop who, at first meeting, seems likely to be a villain.

Ree isn’t the typical American hero who loads her shotgun and heads out to wreak bloody vengeance on the monsters in her life. She has seen what violence brings. Instead, she must bravely pass through unimaginable loss, carry unthinkable burdens, and offer herself as a sacrifice in order to strengthen what’s left of her family. And her declaration of love to her brother and sister is as bright and beautiful as anything you’ll see in the movies of 2010.

True Grit, courtesy of Paramount Pictures.

True Grit, courtesy of Paramount Pictures.

2. True Grit: Is Justice All That We’re Seeking?

The Coen Brothers’ first Western gives us three important stories to consider.

The first is the story of what happens when a young justice seeker, Mattie Ross, hires the ruthless manhunter Rooster Cogburn to track down the vigilante who shot and killed her father. It’s a compelling story. Can 14-year-old Mattie make a journey into the violent, lawless wilderness and achieve justice without losing her soul, her innocence, or her life? Is she wise to take up with such a hard-hearted, hard-drinking man as Cogburn, or that temperamental Texas Ranger named LaBouef?

The second is a tale of two Rooster Cogburns — the one that gave John Wayne his only Oscar-winning performance, and the one that gave Jeff Bridges another Best Actor nomination after he took home a 2009 Oscar for Crazy Heart. In the 1969 True Grit, Cogburn was rather likeable, an iconic Western hero, even if he was a rough-talking drunkard. But in the Coens’ version, the alcoholism can’t be taken lightly, nor can his recklessness. He’s downright dangerous, and it isn’t until the film’s closing scenes that we see evidence of anything like a moral compass.

The third is the story of the American Western. Where Clint Eastwood (Unforgiven) and others have demythologized the West on the big screen, showing gunslingers in wide-brimmed hats to be making bad situations worse no matter how well-intentioned their violence, True Grit delivers a Western with heroics worth applauding. It does so without denying that justice can be bloody and costly. But best of all, it makes gestures of friendship, compassion, and grace burn brighter than any sharpshooting.

The film’s radiant scenery, handsome cinematography, and hymn-fueled soundtrack make this a vivid, hilarious, and haunting tale. We’re stuck with Mattie between the three poles of the law, lawlessness, and mercy, but the starry skies overhead suggest that there is someone watching over Mattie, who will carry her home in his everlasting arms when the strength of her own arms isn’t enough.

Somehow, the Coens accomplish this while still reveling in their love of distinct dialects, cartoonish personalities, oddball supporting characters, and absurd tangents. It’s a Coen Brothers movie through and through, and yet it’s a Western worthy of the label “classic.” It’s too bad that this is the version that went home without any Oscars.

1. Toy Story 3: Were We Made to Be Used or to Be Loved?

Toy Story 3 completes what is arguably the finest American trilogy ever made.

Can you think of another trilogy that doesn’t have a weak link? In the Toy Story trilogy, every scene is beautifully composed, every character perfectly voiced, and every installment full of surprises. The movies inspire laughter from children even as they bring grown men and women to tears.

In the first act of Toy Story 3, leads Woody, Buzz, Jessie, and the rest of the beloved Toy Story characters are carried far from the room of their off-to-college owner Andy, and they land in a daycare. At first, it seems ideal. They’ll never run out of children to play with them.

But as the toys struggle to understand if they should remain loyal to Andy and return to his house, or to fulfill their purpose as toys in the hands of hyperactive toddlers, the story raises tough questions. What are we giving up in our search for a comfortable existence? Do our contemporary luxuries bring about suffering for others? To whom do we owe our true allegiance? As we reflect on the true purpose of toys, let’s inquire about the true purpose of human beings.

Under the direction of Lee Unkrich, Toy Story 3 brings our heroes to a surprisingly harrowing conclusion. As they face seemingly inescapable ruin, they are reminded of how much they care for one another, and the audience — from 6-year-olds to 46-year-olds — is reminded of how much we care for them too.

Reviewing this film for Image, I concluded:

2010 gave us three films that I highly recommend for all ages — The Secret of Kells, Babies, and Toy Story 3. That’s more than usual. American television and cinema feeds American children a steady diet of junk food. But art and entertainment are formative forces, and children need great stories. Pixar’s films continue to reward adults and children alike, giving them something they can enjoy together again and again. And their Toy Story trilogy sets a gold standard for all-ages moviemaking.

What did you think of the 2010 Oscar picks?

Did you agree with Hollywood's choices, or was a film overlooked? Tell us here in this moderated board.