Education Teaching and Learning

SPU and UW Faculty Partner in Literacy Study

Reading Beyond Kindergarten

By Laura Onstot ’03 | Photo by Joshua Bessex / The Daily of The University of Washington

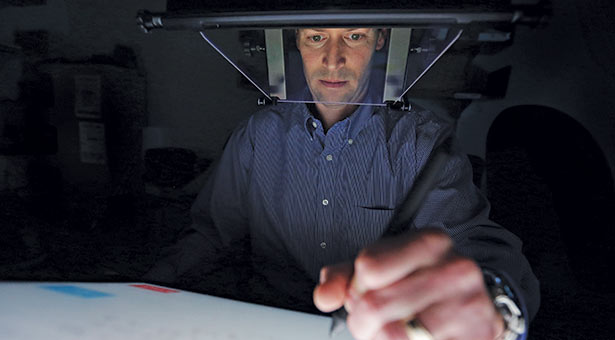

Scott Beers, associate professor of curriculum and instruction, demonstrates a device that measures where the eye looks during writing, used in the literacy study.

Scott Beers watches eyes. Specifically, he watches where children are looking when they write. He has machines that track eye movements, key strokes, and how they move their hands when penning an essay. “What I’m trying to do also is look at reading behaviors during writing tasks,” Beers explains. “I’m trying to take a look at how students interact with their own text as they’re developing it.”

All Beers’ writing observation is meant to make students not only better writers, but also better readers.

Beers, Seattle Pacific University associate professor of curriculum and instruction and chair of the master of education in literacy program, is working on one piece of a massive research effort to help older kids struggling with writing and reading.

In 2011, the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development awarded an $8.1 million grant to a joint project proposed by faculty at SPU and the University of Washington to create curriculum for students in grades 4 to 9 with reading disabilities or challenges. Researchers representing disciplines from literacy and psychology to genetics and brain function are combining forces to look at how to best help slightly older kids who struggle to read.

Teachers can identify students with reading problems “beginning in kindergarten or first grade and know what to do to help them,” says Virginia Berninger, professor of educational psychology at UW and the project director. The problem, she says, is that there are fewer resources for older kids.

Berninger has been working with Seattle Pacific Professor of Education William Nagy for more than a decade and turned to him for help. For this project, Nagy created tests for students coming to Beers for evaluation.

Nagy says one reason struggling readers can still have problems in later elementary and middle school is that the words they are expected to know change dramatically. They become long and consist of multiple parts.

“A word like sleeplessness, looks like it’s 13 letters, and that’s an awfully long word,” Nagy says by way of example. “It’s a very rare word and it’s a very long word, but it’s not a very hard word if you see the parts.”

But some kids can’t see the parts. Nagy wants to give aid to teachers unsure how to help kids who are fighting with those big and unfamiliar words.

Ultimately, instruction is the project’s goal. “At a national level, there’s a great deal of confusion about how to define specific learning disabilities,” Berninger explains. Through this grant and the collaboration between the universities, she hopes to better understand those disabilities and then create “free and appropriate curriculum for all of them.”